Kesang Lamdark and Palden Weinreb

Generation Exile: Exploring New Tibetan Identities

Dr. Clare Harris - Reader in Visual Anthropology, Pitt Rivers Museum and School of Anthropology

Fellow of Magdalen College, University of Oxford

Exhibition presented by Rossi & Rossi hanart Square

This exhibition introduces two exceptional figures who make very different kinds of art and who pursue quite distinct aesthetic agendas. At first glance it might seem difficult to establish a connection between Kesang Lamdark and Palden Weinreb, since the style and content of their works contrast so markedly. However, what binds them together is a passion for formal experimentation and a consciousness of the complexities of identity. As the sons of Tibetan exiles, Lamdark and Weinreb represent a new generation of Tibetans who have been educated and enculturated in the West. They and their works reflect on the fact that it is more than fifty years since the first wave of refugees left Tibet and sought sanctuary in Nepal, India and beyond. The migration of that cohort, following the departure of the 14th Dalai Lama from Lhasa in 1959, has arguably led to the creation of two Tibets: the first, an area within the Peoples’ Republic of China where the majority of Tibetans still reside and the second consisting of a diasporic Tibet that is dispersed throughout the world. In addition there are numerous imagined versions of Tibet: as a nation, as a homeland, as the ‘Western Treasure House’ of the Peoples’ Republic and as the Shangri-La fantasy that was invented in the West in the early twentieth century but has since become a globally recognised phenomenon. All these factors come to bear on how identity is currently envisaged and enacted by Tibetans, wherever they are located on the planet, but they have particular resonance for artists. For them, creating artworks enables a personal exploration of the multiple states of being that they inhabit and a format in which to express Tibetaness in the era after exile.

Art in the Era after Exile

The biographies of Kesang Lamdark and Palden Weinreb hint at the complexity of their own lives and those of many other Tibetans in the post-exile era. They also point to the sense in which ‘identity’ is mobile and malleable, especially for those who have only known what it is to be Tibetan outside Tibet itself or who have undergone a repeated process of movement from one cultural context to another. For example, Kesang Lamdark was born in 1963 in Dharamsala (India) the home of the 14th Dalai Lama and the Tibetan “government in exile”. His parents later moved to Switzerland where Kesang was, in effect, adopted by a German-speaking Swiss family. In his early thirties, Lamdark travelled to the US and studied at Columbia University and the Parsons School of Design in New York. He is now based back in Switzerland. Palden Weinreb, on the other hand, was born in the US and has only encountered the refugee camps of India as a visitor. His mother was among the first Tibetans to arrive in New York (thanks to a Fulbright award), where she met and married a Jewish American. Their child, Palden, developed a passion for art and graduated with a degree in Studio Arts from Skidmore College in 2004. He continues to live and work in his natal city. It is therefore unsurprising that neither artist wishes to be defined solely in terms of their ethnicity and yet they both acknowledge the formative influence of those from whom they gained their Tibetan ancestry. Lamdark recently named a display of his work ‘Son of Rimpoche’ in recognition of the fact that, after many years of exile in Europe, his father had returned to take up his role as the head of a monastery in Tibet. Similarly Weinreb recalls that it was his mother who ensured that he was enveloped by an “atmosphere of the dharma” during his childhood (ably assisted by his American father’s embrace of Tibetan Buddhism). These brief biographical details indicate that it is the transmission of cultural values from one generation to another that is most significant, rather than the crude markers of ethnicity. The artists’ life stories also point to the bi-cultural environment in which they developed. Grounded in traditions stemming from both East and the West and with the critical consciousness engendered by their training in one of the hubs of the contemporary art world (New York), they acquired the facility to experiment with a mixed artistic inheritance and with multiple identities.

The ability to critique inherited traditions and play with established artistic norms is a driving principal in Lamdark and Weinreb’s artistic output. To my mind it arises not only from their bi-culturalism but also from their separation from Tibet as a place. They live and work at a substantial physical distance from the homeland of their parents and yet, unlike the residents of Dharamsala, they do not anticipate return. The narrative of the exile community in India is predicated on remembrance of the old Tibet and the idea that one day they will make the journey back over the Himalayas to their ancestral territory. However, this longing for repatriation is less germane for those who were not born in Tibet or have only visited it infrequently. For the exile generation in the West, Tibet is a powerful idea, a historic locus of religiosity, the source of a shared vocabulary (linguistic and more broadly cultural) and a land they might dream of reclaiming politically or recreating imaginatively through the vehicle of art. But it is not home. Artists of this generation can help to articulate these conceptions and to remake Tibet anew elsewhere but ultimately they do so with several degrees of separation intervening. This means that their work is a translation from the original, so to speak: an attempt to understand and respond to the idea of Tibet in its absence.

Despite the stylistic divergence between the two artists featured in ‘Generation Exile’, their art demonstrates a common interest in these ideas and suggests that the distance from the old Tibet that their parents and grandparents knew can actually be artistically liberating, even if it is also psychologically painful. It is worth recalling at this juncture that such freedom to innovate and reinvent would not have been available to artists in Tibet in the past and it still remains a challenge for contemporary Tibetan artists working in cities like Lhasa, the erstwhile Tibetan capital that is now the administrative centre of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the Peoples’ Republic. Lhasa is also the heart of the ‘Tibetan Contemporary Art’ movement within China and the site where the first experiments in forging a modernist sensibility in Tibet were conceived in the 1980s. The artworks that initially emerged from that city were often either illustrative of Tibetan experience in the Peoples’ Republic or concerned with the iconography of Tibet as place and with the form of the Buddha as an icon of Tibetaness. The works of Kesang Lamdark and Palden Weinreb deviate from these preoccupations in notable ways. From their homes in the US and Switzerland and with the benefit of a post-modernist art education, Lamdark and Weinreb are at liberty to pursue numerous other options. They may embrace the Western romance of Tibet - or not. They may challenge the propaganda directed at their parents’ homeland - or not. They may depict Tibet differently – or even ignore it all together. Or they can make artworks that evoke the multiple worlds that they, as members of the post-exile generation, occupy.

It seems clear to me that both artists have chosen the last of these options but I would also argue that an indirect relationship with the legacy of their Tibetan heritage remains. Let me add that this is my own interpretation as a scholar and admirer of Tibetan culture and a member of the audience for their artworks rather than as an art critic or a mouthpiece for the artists themselves, who inevitably will have other ways of describing their activities and output. But I propose that their oeuvre reprises a fundamental dichotomy at the heart of Western interpretations of Tibetan culture. Put simply, this is the otherworldly versus the earthly, the beautiful versus the bawdy. Comprehension of Tibetan Buddhism in the West was much enhanced in the early days of Tibetan exile as major religious figures migrated to Europe and North America and rapidly began to transmit the teachings of the Buddha (in Tibetan style) to members of their host countries. In the 1960s and 1970s, the publication of some of the most esoteric Tibetan Buddhist texts into English and the foundation of numerous Dharma centres where the philosophic and practice-based aspects of the religion could be disseminated, led to a ground swell of enthusiasm for Tibetan religious culture among non-Tibetans. To abbreviate hugely, Tibetan Buddhism began to be understood as a transcendentalist religion requiring high degrees of intellectual engagement with its philosophical precepts and/or a studied commitment to perfecting ‘techniques of the body’ (as Marcel Mauss would have it) such as yoga, meditation and ritual. In addition, and at around the same time, curious Westerners began to appreciate antique Tibetan artworks in the galleries of museums and in the pages of art historical publications. Once again, their encounters with Tibetan things meant that a broad contrast could be drawn between the ethereal beauty of benign Buddhas and bodhisattvas and the apparently wild, ‘wrathful’ and even sexually explicit forms of tantric Tibetan deities (described as yab yum – i.e. male/female in sexual union). In the old Tibet, these contradictions had happily co-existed. When translated into the new context of the West, they were perpetuated and to some extent exaggerated. So, surprising as it may seem, I’d like to propose that these characterisations can offer a useful way of approaching the work of Palden Weinreb and Kesang Lamdark.

Palden Weinreb

As an artist, Palden Weinreb draws much inspiration from the religious culture and practices of Tibetan Buddhism. In a discussion about his working method, he remarked that he saw them as a source for “self discovery” and described how the memorisation and recitation of potent texts (such as mantras) could activate his creativity and help to focus his intellectual concerns. In the course of our conversation it became apparent that his highly abstract artworks arose from a set of philosophic preoccupations, coupled with a rigorous investigation of the relationship between mind and body, to the extent that the fine lines he etches across paper could be interpreted as the physical trace of a kind of meditative state. Weinreb’s artistic exploration is driven by the need to question the ‘real’ world and to shatter its facades and illusions. This he attributes to the Buddhist (and Hindu) concept of samsara. In Sanskrit the word literally means ‘to flow on’: referring to the cycles of reincarnation and the constant movement through different states of existence. Only when an individual frees himself from attachment to emotion, desire and ego (the illusory state called maya) can the cycle be broken and a more enlightened consciousness be achieved. Weinreb says that his art practice is an attempt to “let go of day to day reality” and to seek out hidden levels beneath the mundane. To this end he has developed a visual language in which dense fields of lines converge and bifurcate, expand and contract, twist and turn. This he posits as a way of interrogating the material world, condensing matter into its constituent parts and thereby demonstrating the linkages between all things that exist in space and time. Weinreb’s artworks therefore often appear to play with the relationship between two and three dimensions, as he delineates a form (such as in Untitled 1- 5 [2011]) that appears to hover in an indeterminate space. Or, as in Flow (2011), they suggest the potential for repetition ad infinitum: the viewer is merely glimpsing a detail of a larger pattern that is timeless and spatially limitless. We have the sensation of witnessing a frozen moment in the passage of time and of gazing upon a micro-component of the cosmos or, as in Entry (2011), a fragment of the architecture of the universe.

In his examination of the effects of pure line, Weinreb can be linked to a major strand in the history of Western art. I refer to the importance of drawing from the classical period onwards, the use of measurements to ensure symmetry, proportion and beauty when depicting the perfect human body (as pursued by Leonardo da Vinci for example when he reworked the specifications of Vitruvius) and especially the deployment of perspective for recreating the appearance of nature in two dimensions. From the Renaissance until the early twentieth century, this mathematical formulation enabled artists to create the impression of ‘realism’ in painting. However, as we have heard, Weinreb seeks to resist the temptations of the ‘real’ and it is the forms of the mind or the cosmological dimensions beyond the earthly realm that he aims to elucidate instead. This actually ties him quite closely to Tibetan artistic traditions, in which strict iconometric rules determined how images of deities should be made. For example, a grid of lines formed the substructure of a Tibetan thangka (scroll) painting in order to ensure its religious efficacy and aesthetic appeal. Realism, of the Western variety, was not required. (In fact, in 2007, Weinreb made a piece called Edifice that specifically referenced this traditional format.) Perhaps even more pertinent are the very precise lines that are necessary for producing a mandala either in paint or in fine particles of stone (the so-called ‘sand mandalas’ of Tibet). Since the mandala is essentially a reconstruction of the cosmos, there was no room for error when Tibetan monk-artists created such potent diagrams for Tibetan monasteries. Like Palden Weinreb, they knew only too well that each individual component of an image had to be perfect since they were ultimately replicating the sublime, transcendent form of the universe. They too were creating something that was far removed from the banalities of the day-to-day and attempting to illustrate a world well beyond that which is visible and tangible to human sensory perception. There are also echoes of the pioneers of European Modernism in Palden Weinreb’s work: such as Paul Klee, who famously took a “line for a walk” to see what it could do, and Wassily Kandinsky whose manifesto for abstract painting, ‘Concerning the Spiritual in Art’, was influenced by Asian art and religion. But above all, in his preference for abstraction over realism and pure line over iconicity, Palden Weinreb is channelling a fundamentally Tibetan Buddhist principle: the pursuit of non-attachment to the material world and the hope of coming closer to the paradise of nirvana.

Kesang Lamdark

If Palden Weinreb’s artworks can be associated with the most abstract, elegant and esoteric features of Tibetan Buddhist culture, then Kesang Lamdark’s are quite the opposite. Lamdark revels in the darker, more disturbing (to Western eyes) imagery of Tibetan temples such as the painted skulls that decorate their walls or the leering, goggled eyed statues contained within them. See, for example, Lamdark’s rendering of a depiction of the Nechung oracle with tongue outstretched and a crown decorated with crania in Tan Tren (2011). Whereas Weinreb, following Buddhist logic, aspires towards the subjugation of attachment and the suppression of desire, Lamdark appears to be specifically interested in engaging with the carnal and the crude. In Mao Muschi Mandala (2011) he forces us to look directly at pornographic images of women, their bodies contorted into hideous displays of flesh. The commodified female body is arranged in emulation of the circular format of a mandala, accentuating the shock value of the work. Even more disconcertingly (for some viewers), portraits of four leaders of China superimposed on a skull comprise its core. Among Tibetan Buddhists this position at the centre of the mandala is usually reserved for a deity. (This is because the mandala is the palace of a deity, as well as a cosmological diagram.) Replacing a deity with the chief architects of Chinese policy in Tibet since the 1950s (from Mao Zedong to Hu Jintao) is as shocking for Tibetan Buddhists as the blatant display of female genitalia is for feminists. The combination of the two is also highly problematic, one imagines, for Chinese patriots. However, the message of this piece is not readily decipherable. It undoubtedly has a political critique at its heart (literally) but Lamdark perhaps also intends to remind us that despite the efforts of good Buddhists to rise above desire, they are still human and may often fail. Equally, the skull could be read as a reminder that even the most powerful Chinese politician is made of fragile flesh that will ultimately perish like all other human bodies.

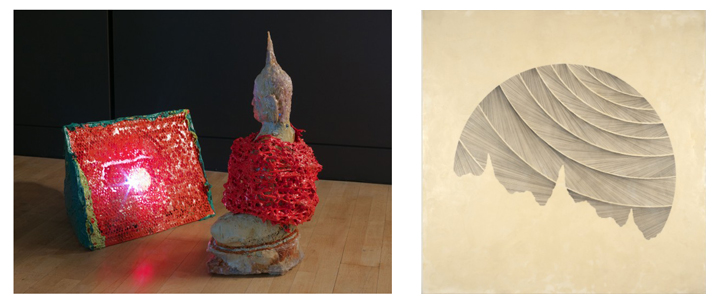

The fact that Lamdark’s interests cover the full spectrum of human experience, from the profane to the divine, procreation to defecation, is apparent in Arabian Toilet (2011) and Dwarf of the Golden Horse-Shit (2007). In these and other three-dimensional works made from plastic, he acknowledges a debt to conceptual artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Nam June Paik (among others). The spirit of surrealism is also detectable in Pink Tara (2008), where an object that should be hard has become fluid and permeable. (In this case a Tibetan Tara sculpted in bronze was the model.) Or as in Vest: Red (2008) where the soft texture of a Tibetan monk’s undergarment has hardened and become rigid. These sculptures suggest that Lamdark is formulating a commentary on the commodification of Tibetan Buddhism both within China and abroad. (For example, solar powered prayer wheels cast in gleaming gold-coloured plastic are currently extremely popular in the Tibetan-speaking regions of China and the Himalayas.) He certainly seems to be intrigued by the potential for converting the remnants of consumerism into objects of beauty and fascination. As examples of art made from found objects, his 2006-2007 beer can series is a perfect adaptation of the Duchampian ready-made. Each can is pierced at the base to reveal a variety of images ranging from a naked woman to a portrait of the Dalai Lama. In order to engage with these works, the exhibition visitor must stand very close and allow their eye to enter the artist’s private peep show. Lamdark thereby converts his audience into voyeurs at a miniature cinema where the featured film is a sequence of images that have tormented or transfixed his imagination.

In experimenting with the illumination of the interior of a beer can, Lamdark began the process that has led to a sequence of new works using plexi-glass and light emitting diodes. In a sense his primary medium is now blackness, from which he removes small particles to reveal a light source behind. The surface of each work is punctured to reveal a host of characters: the Dalai Lama, Chairman Mao, Gene Simmons, a group of Tibetan aristocrats. It is not clear whether these men are to be construed as heroes or villains, since the artist does not discriminate between them, but they undoubtedly reflect the politically charged environment of Lamdark’s imagination. To this observer, the power of these artworks lies less in their imagery (engagingly provocative though it may be), than in the substance from which they are made. The mirroring effect forces the viewer to accommodate his or her own reflection into whatever Lamdark has illustrated and perhaps to consider their own mortality or complicity in the scenes they gaze upon. Most intriguingly, the ghostly apparitions that appear in the blackened plexi-glass are defined by thousands of pinpricks of light. For me this connects to an extraordinary story that Lamdark told me. During his youth in Switzerland, he had been seriously ill and was left with facial paralysis. The Western doctors he consulted could not solve the problem but his Tibetan mother advised him to see an amchi (a Tibetan medical practitioner). The amchi took a pin, pierced the side of Lamdark’s face and movement was miraculously restored. Lamdark describes this as a pivotal event in his life, marking the moment when he decided to learn more about his Tibetan heritage, rather than just persisting with his love of pop, punk, porn and the many other temptations that life in the West had to offer. That search has since taken him to his father’s home in Kham and to Lhasa on several occasions. During those visits he has reconnected with his Tibetan family, collected material to use in his artworks and toured monasteries in the country of his parents’ birth. He has learnt much about Tibetan culture along the way. But he was not aware, (until I told him recently), that a golden needle was traditionally used by monks to insert the eyes of the deities painted by Tibetan artists. With that one stroke, the image became animated: just as life was returned to Lamdark’s face with the tip of a pin and light is revealed in his plexi-glass pictures. I have yet to ask Lamdark whether his depiction of the Dalai Lama piercing the H H Soap Bubble (2011) can be read in a similarly life-affirming way. Sadly I suspect not. Like many of Lamdark’s darkly disturbing works, it proposes that the Dalai Lama’s dream of returning to Tibet is a bubble that will always be burst.

CEH Last edited 7th July 2011