Report from Lhasa

After spending the summer in Tibet, Mechak Project Manager shares

exciting new developments for contemporary Tibetan art in Lhasa

By Tamar Scoggin, Project Manager

A Change of Plans

When I arrived in Lhasa in late June this past summer 2005, I originally planned to stay only a week. I was there as a teaching assistant for a University of Colorado study abroad program, and had ten students and two additional teachers with me. Aside from my students and teaching duties, Lhasa was important to me because I wanted to establish preliminary ties with contemporary Tibetan artists working there, especially those associated with the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild. A special thanks goes out to Mechak board member, Gonkar Gyatso, for introducing me to the GCAG artists via email before I even met them face-to-face.

After a few days in Lhasa exploring the emerging state of contemporary Tibetan art, I realized that I had not given nearly enough time to even begin to give appreciation to the developments going on there this past summer. I was scheduled to depart July 1st. I did not leave Lhasa until July 10th, and even then I still feel like I witnessed just one slice, one moment in an ever creative, ever changing, ever growing movement of contemporary art in Lhasa. As our mission at Mechak is to bring the artwork of contemporary Tibetan artists to a larger world audience, I can tell you that there is much artwork to see, appreciate, (and collect) by artists working out of Lhasa. This first installment of my "Report from Lhasa" is thus an account of what I saw and did in Lhasa during the first week that so inspired a change of travel plans.

The Barkor Gallery

Upon the evening of my arrival in Lhasa, I walked the holy circumambulation route around the Jokhang Temple (see photo below), called the Barkor qura, with my students and fellow teachers.

We had been greeted by rain at the airport, but by the time we began to circumabulate around the Jokhang, the skies had cleared and a rainbow stretched directly over the temple. As we rounded the first corner of the Barkor, tucked amidst the mega-thangka stores and endless booths of tourist curios was a sign for the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild gallery.

We had been greeted by rain at the airport, but by the time we began to circumabulate around the Jokhang, the skies had cleared and a rainbow stretched directly over the temple. As we rounded the first corner of the Barkor, tucked amidst the mega-thangka stores and endless booths of tourist curios was a sign for the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild gallery.While more and more articles are being written about the Guild, none have really hit home the importance of the gallery's location along the Barkor route. To have a gallery of contemporary Tibetan art featured so prominently in this very busy and important area in Lhasa is very encouraging. Not only is this gallery visible to all those who walk by, such as penitents and tourists alike, but the gallery holds a space for contemporary Tibetan art in continuum with the ancient art of the Jokhang and the new, hyper-tourist art that crowds around the Jokhang. For seven years I have researched and followed the movement of contemporary Tibetan art, feeling the same frustration with artists at the lack of public visibility and appreciation of contemporary Tibetan art. To see contemporary Tibetan fine art find its way into the heart of Lhasa and Tibetan culture is very encouraging.

The gallery was already closed that evening, but both my students and I were eager to visit there the next day. The next morning, we stepped out of the frenzy of the Barkor on a hot summer day. It took a moment to adjust to the cool, quiet interior of the gallery, our senses assaulted by the brilliant sunshine, and the crush of tourist curio booths and mega-thangka stores outside. Then, one by one, paintings begin to call out to us. It was not the "lookee, lookee, cheap, cheap!" chant on the streets by Khampa retail warrior princesses; instead there was the sparkling face of a college-age Tibetan girl, steadily gazing at you from a six foot high canvas.

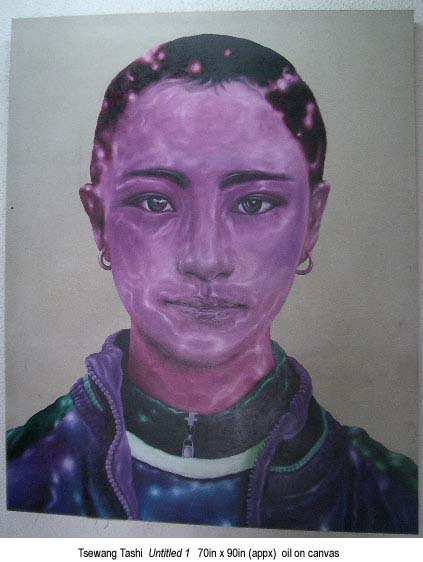

The gallery was already closed that evening, but both my students and I were eager to visit there the next day. The next morning, we stepped out of the frenzy of the Barkor on a hot summer day. It took a moment to adjust to the cool, quiet interior of the gallery, our senses assaulted by the brilliant sunshine, and the crush of tourist curio booths and mega-thangka stores outside. Then, one by one, paintings begin to call out to us. It was not the "lookee, lookee, cheap, cheap!" chant on the streets by Khampa retail warrior princesses; instead there was the sparkling face of a college-age Tibetan girl, steadily gazing at you from a six foot high canvas.  Such portraitures have come to signal a new approach by Tsewang Tashi, a member of the Guild as well as a professor of art at Tibet University in Lhasa. I also saw the series of landscapes Tsewang painted around 2000 that were studies in landscape symmetry, color and grandeur. He has taken the same sense of scale and movement to his portraits, with a technical twist. Fascinated by the possibilities of New Media Art - computer design and installation art in particular - Tsewang takes photographs of "everyday Tibetans," edits the photos in Photoshop, then paints the re-designed photograph (as shown in the piece below). He also teaches such "new media" techniques and possibilities to his students too. The idea is to plug into the daily life of Tibetans in Lhasa, illustrate it through images and influences they have around them everyday.

Such portraitures have come to signal a new approach by Tsewang Tashi, a member of the Guild as well as a professor of art at Tibet University in Lhasa. I also saw the series of landscapes Tsewang painted around 2000 that were studies in landscape symmetry, color and grandeur. He has taken the same sense of scale and movement to his portraits, with a technical twist. Fascinated by the possibilities of New Media Art - computer design and installation art in particular - Tsewang takes photographs of "everyday Tibetans," edits the photos in Photoshop, then paints the re-designed photograph (as shown in the piece below). He also teaches such "new media" techniques and possibilities to his students too. The idea is to plug into the daily life of Tibetans in Lhasa, illustrate it through images and influences they have around them everyday.Tsewang Tashi is, however, but one of nineteen artists in the Guild. A further look around the Barkor gallery reveals the tremendous variety of styles, techniques, and talents of the artists. There is Dedron, one of the two female artists associated with the Guild, with her whimsical yet highly-technical and socially-saavy small canvas paintings, such as this piece shown below, titled "Night Scene."

Dedron was one of five women artists featured in Geden Choephel Artist Guild's first all-woman exhibition in 2003. She also moonlights as a teacher for blind students, and her pieces made you feel like you were exploring the canvas by fingertips in your eyes.

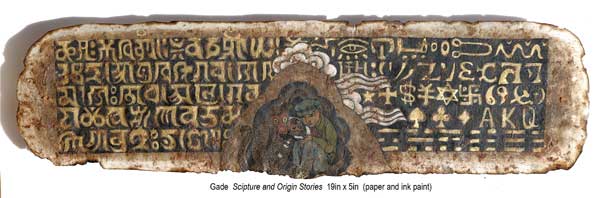

Dedron was one of five women artists featured in Geden Choephel Artist Guild's first all-woman exhibition in 2003. She also moonlights as a teacher for blind students, and her pieces made you feel like you were exploring the canvas by fingertips in your eyes. In the same small gallery on the second floor, I found Gade's series of pieces painted and drawn on the same type of paper as Buddhist scripture books. Framed between two pieces of plexiglass, decorated pages appeared like artifacts. Many of them read as testimonies, riddles, even comic strips, all of them were fascinating to regard.

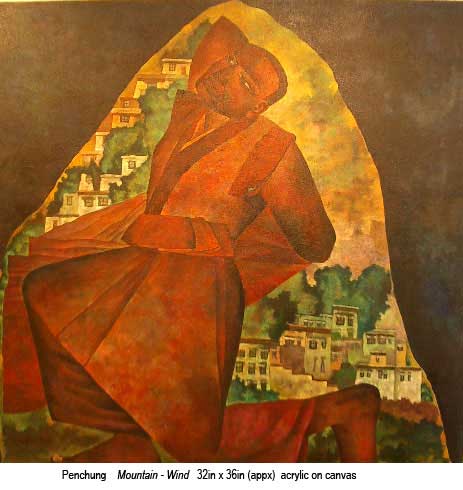

There are a variety of works by Penchung, another artist who I found doing exciting, breakthrough work as well. In the other, larger gallery on the second floor, I was drawn in by Penchung's "Mountain" series. Inspired by the landscape of mountains that surround the valley of Lhasa, Penchung uses the spatial dynamics of mountains to build his painting (see image right). By depicting a monk in the wind in the shape of the mountain, Penchung also suggests the shape and symbolism of torma, painted sculptures that are made out of butter and created as an offering, especially during the Tibetan New Year.

There are a variety of works by Penchung, another artist who I found doing exciting, breakthrough work as well. In the other, larger gallery on the second floor, I was drawn in by Penchung's "Mountain" series. Inspired by the landscape of mountains that surround the valley of Lhasa, Penchung uses the spatial dynamics of mountains to build his painting (see image right). By depicting a monk in the wind in the shape of the mountain, Penchung also suggests the shape and symbolism of torma, painted sculptures that are made out of butter and created as an offering, especially during the Tibetan New Year.

Also in the larger gallery were paintings by Tsering Nyandak - my future translator and colleague (see image on left). In Nyandak's textured paintings, Tibetans drink beer or watch television in a style that teeters masterfully between whimsy and despair. An apprentice of Tsewang Tashi's, Nyandak is now a self-styled, independent artist, as well as a leading figure, both artistically and operationally, in the Guild.

I was also impressed by paintings by Chinese artists; there are three in the Guild. Indeed, what makes GCAG even more meaningful, and complex, is that the cooperative of artists and exposure of their work together both clarified and challenged what I previously took for granted as contemporary "Tibetan" art. In conversations yet-to-come with both Tibetan and Chinese artists, we would explore an even wider definition of contemporary art inspired by "Tibet", and what such exhibitions, international and cross-cultural in scope and identity of artist, might look like. "Tibet," with its extraordinary landscape and cultural mystique, has inspired myriad artists, writers, poets, filmmakers, and curators who have in turn inspired countless audiences through time and from around the world. While I am intrigued at the possibility of exploring larger themes within the definition of contemporary Tibetan art, we have only begun to explore what artists are doing in Lhasa, the historic capital and cultural heart of Tibet, much less those who were born and raised as Tibetans in Lhasa.

During my first visit to the Barkor Gallery, I met some of the artists hanging out there: Gade, Shelka, and Tenzin Jigme. After I introduced myself, we pulled out floor cushions and sat on the cool cobblestone floor. Between sips of hot tea, I asked them general questions about their organization as an artist cooperative/guild. It turned out that based on the initial success of their Barkor gallery, which opened in August 2003, the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild had recently opened a sister gallery in May 2004. Interestingly, this new gallery was located in the courtyard of the Yak Hotel, a mainstay hotel for foreign tourists in Lhasa (it also happened to be the hotel I stayed at when I visited Lhasa almost seven years ago). This new gallery was yet another strategic public location for the GCAG artists, this time associated with a well-frequented hotel in Lhasa. Gade invited me to check out the Yak Hotel gallery the next day, as well as meet Tsering Nyandak who could serve as my translator and guide to the Guild.

The Yak Hotel Gallery

The Yak Hotel GalleryWhen I stayed at the Yak Hotel almost seven years ago, I remember East Beijing Road as a quiet, almost dusty street where most of the moving vehicles were military or public transportation, overshadowed by the Potala Palace about a mile down the road from the Yak Hotel. Now, East Beijing Road is lined with department stores, hotels and restaurants, while taxis, tour coaches and private cars, rickshaws and pedestrians battle the asphalt. My first attempt at crossing this road was nothing short of a race across, dodging taxis and rickshaws, while other pedestrians simply strode between vehicles and bikes. When my visits to the Yak Hotel became a daily experience, I too soon learned the timing and cool swagger of crossing East Beijing Road at its busiest.

When I stepped into the courtyard of the Yak Hotel upon my first visit, I was reminded of what it had been like to enter this courtyard for the first time seven years ago. As a college student myself at the time, I had just spent three weeks trekking in south-central Tibet with my classmates. Even back then, Lhasa was a bustling metropolis compared to the villages we had been in. A young German man had approached us, asking us where we had just come from. One of my fellow students had stared at him dumbstruck for a moment: he was the first English-speaking non-Tibetan, other than ourselves, we had seen in two and a half weeks. Tibet has been traveled from the West and the East for millennia, but has also remained geographically unique and culturally distinct. So much so that tourists still draw great attention in many Tibetan areas in Yunnan, Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu provinces and the Tibetan Autonomous Region (T.A.R.). Nevertheless, the numbers of tourists from both the East and West who are traveling to Tibet each year is growing, seeking to experience its extraordinary landscape and cultural mystique. As you can imagine, there is now a booming tourist industry, especially in Lhasa, offering everything from pilgrimage or mountain climbing treks, to factory-produced thangkas, to audio tours of the Potala Palace.

The Gedun Choephel artists have found that most of their work sells to tourists - hence the strategic locations of the Barkor and Yak Hotel. And hence the prominence of paintings in their galleries: they are easier to mail to the transient buyer. It was interesting to note how such a subtle detail influenced what the Guild chose, and was capable, to sell. In a store adjacent to the main exhibition gallery, I found further evidence of how the Guild had to operate as a business to their main source of customers. Hanging from walls and resting in glass sales cases, I found the usual, yet ethnographically fascinating, assortment of cultural souvenirs offered in Lhasa: turquoise jewelry, handmade paper, ritual items like bells and vajras, thangkas, carpets, and various wood carvings.

Beyond the income earned when a painting was sold (artists donate 10% of sales to the Guild), this gift store was meant to act as additional income to help get the newly-opened Yak Hotel gallery off the ground.

The other half of the Yak Hotel space was the actual exhibition gallery. Consisting of one room with a large divider in the middle that also acted as painting storage unit inside, this brighter, more modern exhibition space complemented the antique charm of the Barkor space. As I walked around this gallery for the first time, I got to admire a whole new batch of paintings by artists whose work I was only beginning to put together based on information on wall labels.

Historic Continuum, New Beginnings

During my first visit to the Yak Hotel gallery, I met Nyandak and he immediately began helping me by translating a conversation with GCAG artist, Norbu Tsering ("Nortse", see photo below). When I was told that Nortse would be holding his first solo exhibition as a member of the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild on July 2nd, I realized that with my current travel plans I would not be able to see this exhibition. Based on the strength of his work, as well as that this exhibition would be the first publicized event for the Yak Hotel gallery (flyers were up around town already), I felt that missing this exhibition might be something I would greatly regret. When I inquired more into his background and found out that Norbu Tsering had been a founding member of the Sweet Tea House Artist Association in Lhasa back in the early 1980's, I knew that a new development in the history of contemporary Tibetan art was about to take place.

As short and unknown as the history of contemporary Tibetan art is, the Sweet Tea House Artist Association (STHAA) of Lhasa is one of the more well-known moments. Started in the mid-1980's by the first wave of Tibetan artists returning to Tibet after receiving art training at the Central Art Academy in Beijing, the goal of the STHAA was straight-forward: to start a movement of contemporary art unique to the Tibetan experience. Aside from experimenting with their own set of aesthetics and techniques, the Sweet Tea House artists also defined themselves as a cooperative of artists who were exclusively Tibetan - they might be Muslim, Buddhist, or even atheist, but they all first identified as ethnically "Tibetan." Also among the distinguished alumni is Gonkar Gyatso, an artist now living in London who is both on the board of Mechak and a featured artist in Mechak's currently-traveling exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art from outside Tibet.

From 1984-1986, the Sweet Tea House artists exhibited, as the name suggests, in tea houses around Lhasa. When the Lhasa art market and cultural life declined in 1987 due to social unrest, the STHAA disbanded. Twenty years later Nyandak took me to one of the old tea houses for a lunch of yak curry complemented with copious amounts of sweet tea. As I gazed around the dark walls of the tea house, slightly hazy from cigarette and cooking smoke, I tried to picture what an exhibition must have looked like here. Artists like Gonkar went on to start his career anew in the West, while others found art related jobs in design and teaching. When the Gedun Choephel Artist Guild was founded in August 2003, many first-wave contemporary artists, such as Nortse, gravitated toward the Guild and began painting for themselves again - sometimes after more than ten years of not painting at all. They now had their own gallery spaces to call their own (see photo to right).

Knowing Nortse's historic involvement with the contemporary art movement in Lhasa, I realized how important his solo exhibition was in terms of his own career and the signaling of a new era of art and cultural life in Lhasa. When I was asked to help curate the exhibition, I was moved by the invitation and my own personal history of working with contemporary Tibetan artists.

Knowing Nortse's historic involvement with the contemporary art movement in Lhasa, I realized how important his solo exhibition was in terms of his own career and the signaling of a new era of art and cultural life in Lhasa. When I was asked to help curate the exhibition, I was moved by the invitation and my own personal history of working with contemporary Tibetan artists. When I first began interviewing artists (like Sherap Gyatsen, see below photo) and documenting their artwork in Dharamsala, India, in 1999, I was an undergraduate college student who, longing to be an artist herself, was instead training to become an anthropologist who studied artists. While I lived vicariously through the artwork and creative process of the artists in Dharamsala, I also came to feel a great sense of empathy toward them as well. Seven years ago even Gonkar Gyatso (one of the more well-known outside artists) was a struggling artist who had just started art school in London.

While awareness has since grown about the emerging contemporary Tibetan art scene in Lhasa through articles in The New York Times and exhibitions in Beijing, Hong Kong, London and New York City, artists working outside of Tibet are still working to have their voice heard. Members of the GCAG artists have their own gallery space, have exhibited internationally, and are represented by galleries in London, New York, and Santa Fe. Such collaborations and exposure have only begun for other artists. This past February 2004, Mechak's inagural exhibition Old Soul, New Art, which opened in New York City, was the first-ever exhibition bringing together a group of artists working outside Tibet.

Since my encounter with contemporary Tibetan art in Dharamsala seven years ago, I have had a chance to work with artists living in London and Australia, as well as those in Lhasa. If you had told me during those formative months in Dharamsala that I would someday curate any exhibition of contemporary Tibetan art - especially one in Lhasa - I would have considered it impossible. Impossible, mostly because Lhasa was still very much a closed society. Nowadays, Lhasa has opened up through rising consumerism and tourism in China, and such openness has allowed for an art and culture life to flourish anew along the Barkor route and East Beijing Road. I am honored to not only be a witness to these encouraging historical changes, but to assist in their benefit as well.

In addition to being asked to guest curate Nortse's exhibition, the Gedun Choephel artists asked me to give an informal lecture on the contemporary Tibetan art scene beyond Lhasa. The temptation to change my travel plans had just doubled. It had taken me almost seven years to return to Tibet. Now, I was not only here, but so much was happening with the artists, and we were all hitting it off so well. I had come seeking the acquaintance of a few artists, and instead I found myself in the midst of exciting developments for contemporary Tibetan art in Lhasa.

After a particularly introspective walk around the Jokhang, meditating on whether or not I should stay, I made up my mind. I called the airline and cancelled my July 1st departure. I then grabbed my notebook and camera, and headed toward the Yak Hotel gallery, artfully dodging cars and rickshaws across East Beijing Road.

***