By Yangdon Dhondup:

I first met Gadé on a cold November day in 1994. After showing me round the Fine Arts Department

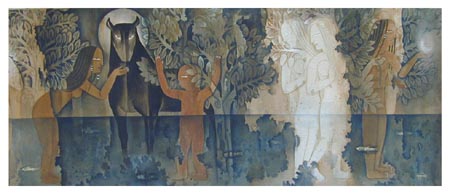

of Tibet University, where he works as a lecturer, we looked at some of his own art works. His paintings

were enthralling. Some depicted elegantly posed figures swathed in warm colours while others were of

delicate bodies framed within the silhouette of a resting Buddha. Gadé uses a paint technique of mixing

mineral stones, and his paintings therefore carry an earth-tone colour scheme, occasionally accentuated

with bright hues. The Buddhist symbols imbued his works with a sense of serene beauty and mystery.

Gade Bathing

During lunch at the newly opened Indian restaurant on Beijing East Road, he tells me that a postagestamp featured one of his paintings, a rare opportunity for a Tibetan artist living in Tibet. The Indian

restaurant was owned by a Tibetan and a Nepali businessman, one of the joint-ventures which boosted

the economy and the mood of Lhasa residents following the years of repressive control. The novelty of

being able to eat different sorts of spiced curries while watching Tibetan girls wrapped in colourful

saris dancing to the music made the restaurant, for a short while, the talk of the town. It seemed

fitting that we had chosen this restaurant, for it represented Lhasa, Gadé and in some ways also

myself - a hybrid mixture of Tibetan, Indian, Chinese and Western influences.

Over the past twelve years of loosely following Gadé's life and work, he has remained consistent with

his technique of using paints made from stones, as if trying to literally ground his works in native soil.

His focus, however, has shifted. In his early works, his figures were mainly inspired by Buddhism.

Gadé admits that Buddhism had a strong influence in his earlier works and how these depicted a

mythical Tibet which only existed in the imagination. He says, "What I really wanted was to paint my

Tibet, the one I grew up in and belong to." His current works thus include elements of present day

Tibet - a monk comfortably sits next to a PLA soldier, and miniature portraits of Elvis Presley, Sherlock

Holmes and Mickey Mouse are painted on a faint lineation of a Buddha. The juxtaposition of the local

with the global is not only Gadé's preoccupation - in this he represents a new generation of Tibetans

that is comfortable with both the traditional and the modern Tibet. "My generation has grown up

with thangka painting, martial arts, Hollywood movies, Mickey Mouse, Charlie Chaplin, Rock 'n' Roll and

McDonalds", he says.

Indeed, the likes of Gadé grew up in a time of political and socio-economic reforms. They have heard

only from their parents of the disastrous political campaigns which China and consequently Tibet

underwent. Many of them also belong to a group of privileged Tibetans sent to China for their education.

Gadé, for example, was trained in Western and Chinese styles of painting at the Central Fine Art

Academy in Beijing.

Gade Birth New Scripture #30

The Lhasa they know has evolved over time from an ancient city into a modern metropolis where thepast and the present co-exist. Early each morning, young and old Tibetans reverently queue in line to

get into the Jokhang, Tibet's most sacred temple, while spending their nights in glittering Karaoke bars

and fancy night clubs. Artists like Gadé, Dedron, Tsewang Tashi, Nortse, Tsering Nyandak, Tsering

Dhondup or Zhungde are constantly switching between these two worlds and express in their works

the ongoing negotiation between being a traditional and a contemporary Tibetan. Some even do not

feel obliged to express something "Tibetan" in their works and although psychically based in Lhasa,

their works include cultural references from different parts of the world. The result is innovative and

shows a creativity and vitality not seen before in traditional Tibetan art forms. Undoubtedly, their works

mirror the present state of Tibet, a place full of beauty and contradiction.

The history of contemporary Tibetan art starts with the controversial scholar, monk and traveller

Gendun Chophel (1903-1951), whose paintings and sketches, especially the ones he produced

while travelling through India in the 1930s and 40s, clearly exemplify his innovative and inquiring mind.

His student and friend, Amdo Jampa (1911-2002), became the first Tibetan to study art in China.

Amdo Jampa's works, such as the murals painted in the early 1950s inside the Norbu Lingka, the

summer residence of the Dalai Lama, were revolutionary in the sense that he combined traditional

Tibetan styles of painting with photo-realist portraits.

The styles used by the younger generation are diverse, ranging from traditional paintings to realist,

abstract or expressionist pieces. In creating such art works, these artists, like their forerunners, are

pushing the boundaries of what is known of "Tibetan" art.

Many might fear that such interfusion will destroy the little of Tibetan culture that is left. But to

locate authenticity only with those who produce traditional art is to deny the existence, history

and experience of those like Gadé. He clearly disagrees with being forced into a defined category:

"Now", he writes, "We cannot place our identity in a fixed area, as there are too many things that

have happened." His comment, which he made on a painting depicting the arrival of the first train

to Tibet in July 2006, should be a reminder for us when we consider defining a "Tibetan" or "Tibet".

The issue of authenticity does not seem to torment the artists themselves but more those who

want to confine Tibetans into certain constructed identities.

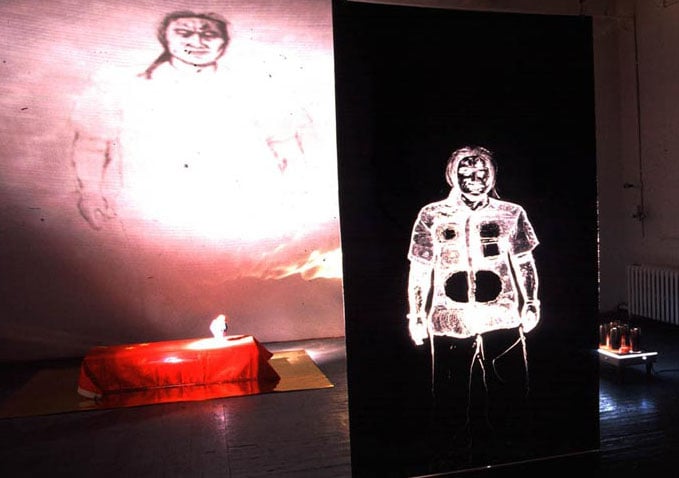

Kesang Lamdark Killergrass Kesang Lamdark Self Portrait

How else can we explain the silence concerning the works of, for example, Kalsang Lamdark, a

Tibetan born in India, raised in Switzerland and trained in the States? Nobody seems to be

interested in discussing Lamdark's work in the context of contemporary Tibetan art. In his case,

is authenticity only located with those inside Tibet or is he culturally too close and therefore of

no interest? In any case, Lamdark clearly seems to have transgressed the borders of constructed

identities, hence the silence.

Whether such art works are produced inside or outside of Tibet, these artists are breaking away

from the concept of what is commonly known and represented as "Tibetan" art. Their works,

however, reflect an important aspect of contemporary Tibetan culture. For those who care to see

a Tibet which might not necessarily portray their own imagines of the land but those of the

Tibetans themselves, the works of these artists are worth careful consideration, for they represent

the present state of Tibet and its people.

Yangdon Dhondup graduated in Chinese Studies from the School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS),

University of London. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at SOAS.

Her research interest covers contemporary literature, music, art and life histories

Gadé in  www.artareas.com

www.artareas.com

Gadé: "Modern Art in Tibet and the Gedun Choepel Artists' Guild" in Visions From Tibet. A Brief Survey of

Contemporary Painting. London: Anna Maria Rossi and Fabio Rossi Publications, p.17.

Gadé. Railway Train in  www.asianart.com/pw/gallery1.

www.asianart.com/pw/gallery1.