What is this? Let that Moment Become Eternal!

New Works by the Tibetan Artist Losang Gyatso

by

Tsering Woeser

Translator’s note: The Chinese original of this essay was first published in Beijing Spring 187:67-72 (December 2008). To access its electronic and audio editions, go to  http://beijingspring.com/bj2/2008/320/20081126124847.htm.

http://beijingspring.com/bj2/2008/320/20081126124847.htm.

Likely they had known that that moment would appear not only on televisions in many countries but also through the omnipresent internet connections. Let alone other venues, the first ten pages of a YouTube search for “Jokhang” can lead to at least nearly a score of videos that were from the footage recorded that moment. They must have known it. They must have been told in advance that reporters from foreign media (a couple dozen of them) would arrive in Jokhang that morning – for the first time in seventeen days since the temple was closed on March 10th. Everyone was ready. Authorities had assigned some of the most obedient Tibetans to cooperate. Yet, “Those worshippers, they are all cadres in disguise; it’s a cheat….,” they, those monks in Jokhang, told the truth at that moment. Apparently, they had been preparing to speak out. Nevertheless, it is impossible that they had not thought of the unpredictable price they would have to pay by doing so. As a result, their participation disclosed the episode which was orchestrated to give the impression that Tibetans are fortunate and free. While rushing out to surround reporters, they desperately yelled: “No, we don’t have freedom! The Dalai Lama is innocent….” The reporters who had been invited to tour the tightly controlled Lhasa finally saw the act which had the most shocking journalistic effect; in a matter of minutes, the authorities were left no place to hide the intention behind the show they had wanted to stage. That shocking moment was said to have lasted about fifteen minutes. I remember clearly the indescribable pain which I felt that evening when watching the short segment of that moment on the internet. I was reminded of this line by Anna Akhmatova – “The heart gives up its blood.”

Nevertheless, most likely they have not known that, months later, that moment had been recreated by an artist. Although art should be unbounded by boundaries of nation and artists are often not tied to their native place -- as deities are not confined by their sex, I would still rather refer to this artist in a more restrictive and somehow assertive manner. He, Losang Gyatso (la – according to the formality of our tradition) is a Tibetan artist. The point here is “Tibet.” Although he now lives Washington, DC, although he has not returned to his native place in the Snow Lands for the past forth-nine (and soon fifty) years, he is the Tibetan artist who has through his work of art transformed that moment into six images. In the meantime, he has also created another six images to note another moment in the Labrang Monastery in Amdo, which was as crucial as the one in Jokhang. These twelve images are all modeled after monks who are recognizably Tibetan and native, and they are a great deal similar to each other. Yet, they are also apparently different. One image is more so than the other in overwhelming their beholders. I can nearly hear their voiceless cries piercing through the internet; my ears hurt.

Once, during the years of the Yezhov Terror in Soviet Union, Akhmatova was waiting in a queue to see her son in prison. Another woman who was also in the queue for the same reason whispered in her ear: “Can you describe this?” “Yes, I can,” Akhmatova said. A sad hope crossed her face, and the woman smiled. Later on, Akhmatova had these lines to start the Requiem:

No, not under a foreign heavenly-cope, and

Not canopied by foreign wings --

I was with my people in those hours

There where, unhappily, my people were.

The Soviet era of terror which Akhmatova wrote about is remote to a reader like me. Yet, I have to say that the pain and sorrow there and back then survives because of her poem. Similarly, having exiled myself from my beloved Snow Lands, I want to say that the pain and sorrow there and back then is remembered because of the twelve Tibetan images created /restored by Losang Gyatso.

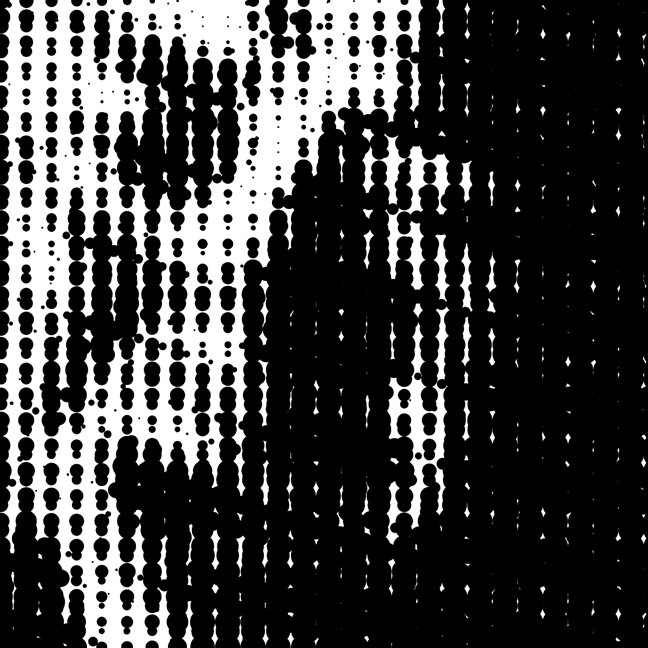

According to the introduction of the new series posted on Losang Gyatso’s website, all of the twelve images are adapted from digital videos, manipulated on the computer screen, and then silk screened onto aluminum sheets. Each of them is 18 by 18 inches in size. Aluminum sheets? Would that be a metal which, according my Google search, is somehow heavy, bright, and sturdy but also soft and malleable? I called an artist in Beijing to ask his opinion. He said that some artists do like to use materials of this sort, mentioning an exhibition he invited me to see last year. In that exhibition, black-and-white photos taken during the 1937 Nanjing Massacre are silk screened on the surface of shining stainless steel. Alright, that material is perhaps not the most important element; the artist could have used other materials to express what he had in mind. Nevertheless, I also felt that Losang Gyatso must have thoughtfully decided on using silk screen and aluminum sheets to represent those twelve Tibetan images.

I was not sure whether I had thought too much. After all, I have not known how Losang Gyatso usually goes about his work of art. Perhaps the artist has been used to working on aluminum sheet – just like other artists use canvas for oil painting, cotton cloth for thangka, and rice paper for ink painting. Yet, on his website are also his earlier works. They are so colorful and brighter than even mural paintings in monasteries. Because of them, I recall these lines from a poem I wrote a long time ago – “what a beauty, what a beauty, / unspeakable beauty, / beauty beyond imagination, / my past, / our past, / useless beauty, beautiful, beautiful, it’s truly beautiful, / what do I have to give to reclaim that beauty?” To me, these lines explain why I cannot cease loving Losang Gyatso’s paintings – simply because I see in his paintings the disappearing Tibet which he treasures and the Tibet which he describes as having been in his DNA. That Tibet is undoubtedly pleasant to Losang Gyatso’s audience. Yet, to a viewer like me, I feel the same loss which I once tried to capture through those lines of my poem.

While first encountering this new Jokhang-Labrang series by Losang Gyatso on his website, I had no idea about when he had started it. The moment in Jokhang happened on March 27th, and what occurred in Labrang took place on April 9th. Then, this new series of twelve images, entitled Signs from Tibet, must have been the most recent works by Losang Gyatso. I am surprised by how different these works look – from all of his earlier ones posted on various websites. The new images are so different and abrupt that they look as having been made by someone else. I have to say that, at the first glimpse and when I returned to them later, staring at these images has by no means been a pleasant experience. To put it bluntly, I actually feel very uncomfortable with their visual effect. They are sharp, making one feel dizzy…. Moreover, the dense dots constitutive of these images are seemingly roaming; the blank and huge black space appears to be able to engulf you, drag you down together with it! On the other hand, one only needs a single glimpse to realize the origins of each of these images, let alone that they are all numbered from Jokhang No. 1 to Jokhang No. 6 and then from Labrang No. 1 to Labrang No. 6. The repeated titles are simple and straightforward. I should make it clear that not only I but also many other Tibetans recognize what is in these images. As for others, whether they can see what we see in these images is difficult to decide. I do not mean to be judgmental. It is simply a reality that, without a shared cultural background and particularly without feeling that we have been on the same boat since this March, people can be completely irrelevant to each other.

These images are not comforting to one’s eyes. I had to first download them before viewing them in different sizes on my computer screen. I kept shrinking these images. Such a process turned out to be a very overwhelming experience. The scattered dots on the screen would be gradually condensed into a human face – so passionate and sincere, as if still demanding for your attention, listening, respect, and action to cease suppression. That moment is brought back to life. But when I accidentally keyed in an extra zero, the image in size 100% suddenly became 10 times larger on the screen. I was stunned by this unexpected enlargement, unable to do anything besides stare at the screen saturated with disordered dots and chunks of disturbing black-and-white. Nothing left or remained intelligible. Where is that moment? Where is each of those human figures?

Between the reduction and enlargement, between the restored and lost realities, as Yeats said: “….All changed, changed utterly:/A terrible beauty is born.” And as Yeats also wrote: “….for all that is done and said / We know their dream….”

* * *

I have to let you know how much the affinity I feel with those six Jokhang images. That night while sitting in front of my computer to repeat the short video of that moment, I could not stop weeping. Inside Jokhang everything was familiar – the mural paintings restored after the Cultural Revolution, paint-cracked doors and windows covered with the smoke of butter lamps and, moreover, the faces of those monks. Nearly every one of them I had met, and I had even had conversation with some of them – although I cannot remember what we had talked about. I had visited the dorm rooms of some of them. Flowers blossomed in front of the window of those rooms, and inside the rooms there were televisions and computers. As a matter of fact, monks in Jokhang tend to live in a better material condition. They are young; many of them have grown up in the monastery – residing with the older monks who are usually their relatives. Once reaching the age permitted by the government, these young monks begin to dress in monastic robe. Some of the young monks who participated in the incident on March 27th were new recruits from recent years. As I remember, the quota which the government allows has been about 120 monks at any give time for Jokhang. Those who escape or decide to withdraw from the monastery would be replaced by others on the waiting list for recruitment. Having been so close to them, I was shocked and touched by the action they took on that day, and I later discovered that I had not been alone. Others were similarly moved by them. After all, Jokhang is like a brand name. Being a monk in Jokhang is not the same as in any other monastery. The quota guarantees their livelihood from within the state system. Therefore, these monks must have been driven by their courage and belief to come forward; it also suggests the way in which they must have felt to be left no other options.

August, when Beijing showed off its imperial prosperity through the Olympic Games, I returned to Lhasa via Amdo. The third day when I was there was a Wednesday, the most precious day of the week. Others might not know, but Tibetans all say that Gyawa Rinpoche (His Holiness the Dalai Lama) was born on Wednesday. What passed on orally has become custom. Every Wednesday, smoke from burning juniper leaves as a form of offering is particularly dense in the city, and prayers are more intense. Yet, I had not imagined that after March 14th this year, there were still that many Tibetans who came out on Wednesday to light the offering for the One they deeply missed. Heavily armed police and soldiers were everywhere on the streets – walking and standing around to ensure that they were intimidating and in total control. Passing through soldiers and their guns, I entered Jokhang in a rush. I could not recall how many times in these years I had stepped inside Jokhang as a traveler hurries home. This time, while in a hurry again, I also wanted to know what had happened to those monks – after they told the truth to the reporters from the foreign media on March 27th.

Next to the gate on the right, several monks whose job was to sell tickets to the tourists were sitting around as they usually did in the past. As it happened, they were all the residential monks in Jokhang whom I have known for years. I knew the names of each of them. Surprise was on their face when they saw me, and I had to keep my own emotion at bay. We could only say “Depo yinpey (Are you all right)?” to each other and were unable to go on our endless chats like we would do in the old days. I was crying and barely remembered what else happened afterward on that day. Impressions of blood and fire since March came back to me; they made it harder for me to stop crying…. Towards Jo Rinpoche, whose face looked heavy and serious, I bowed down deeply three times. I could hear the dull sound of my own forehead touching the hard and cold floor. I was shoulder to shoulder with the crowded pilgrims. I was pushed left, I was pushed right, getting so close that my forehead was reaching the body of Jo Rinpoche in his lotus position: Oh, Jo Rinpoche, dressed with precious stones, wrapped in golden silk, exhaling the fragrance of burning incense, in front of him were mounds of khatas and coins, and also mounds of our tears. Yes, it was right there where I ran into one of the monks who had shouted out with tears in the faces of those foreign reporters, and who is also among the images of Losang Gyatso’s Jokhang series. I knew that he was not a ku-nyenla in charge of the butter lamps and burning incense in the main shrine. He emerged all of a sudden, standing next to the ku-nyenla, and with his hands folded as if he was offering a prayer to Jo Rinpoche. But…, but he was staring at me. I was in shock, staring back at him. I recognized him, but what could I say to him? Surveillance cameras were everywhere and, in the crowd, were also pilgrim-disguised sopa (spies). We were watched, high alert could not help! With tears in his eyes, he stared at me and apparently wanted to say something. But what could we possibly say? We were so close to each other; I could not walk away without asking: “Depo yinpey?” He nodded with tears. “Thukje-chey, thukje-chey (Thanks, thanks),” I blurted out, and my own face was covered with tears. I could only walk away with my head bending low. Nevertheless, it is a relief to realize that he remained in Jokhang. Another monk whom I had known for years came to me, at a risk reminding me: “Aja (Sister), don’t ask anything here, and don’t say anything….” On the second floor in Jokhang, I ran into another monk. He was another one of those speaking out during the visit of the foreign reporters on that day. He is also among the images of Losang Gyatso la’s Lhasa series. He was with several other young monks. They must also have been there at that moment. He gave me a weak smile -- the kind of smile which conveys a tremble with fear, and the kind of smile which you would rather not see. I was unable to utter a word, and I walked away crying. Where were the surveillance cameras? Where were the sopa? After all, I saw them in Jokhang. That was enough.

As for the other six Labrang images by Losang Gyatso, I have only been in the Labrang Monastery three times and had not known any of the monks in those images. Nevertheless, I came to know Lama Jigme who is about my age. He used to be the deputy director of the monastery’s management committee. In 2006, he secured a passport to travel to India to attend the Kalachakra Initiation by Gyawa Rinpoche. He was detained for more than forty days after returning from that trip. Finally, they had to release him and allow him to return to the monastery because of the lack of evidence to prosecute him. Without disguising his identity, he provided a detailed testimony on what has happened since March this year in a most recent video in which he alone spoke for twenty minutes. (It’s video again!) During those intense weeks, Lama Jigme himself was arrested again without charge, interrogated with torture. He was nearly starved to death in the detention. In the video he talks about that day on April 9th when foreign reporters visited the monastery, approximately two scores of monks rushed out with hand-made snow-lion flags, repeating that “we demand human rights; we have no human rights….” Afterwards, most of those monks were arrested and severely beaten. A monk whose legs were broken has remained disabled since then. Several monks were tortured with electric prods sticking into their mouth and have since then suffered with mental illness. As for Lama Jigme himself, no one seems to have known about his whereabouts after that video went public through the Tibetan Service of the Voice of America. Some people said that he had gone into hiding and others said that he had been under house arrest. Yet, apparently he must have returned to the monastery recently, because more than seventy armed soldiers and police surrounded his house in the monastery around the noon hour on November 4th. They took him away. According to a witness of this most recent development, outside the house of Lama Jigme were military vehicles and police cars with the sirens on. His whereabouts and future is unclear….

According to an Amdo friend of mine, more than a dozen of those Labrang monks who protested on April 9th had fled. Hiding in the grasslands, they were protected by nomads. Yet, when some of them tried to contact the outside world with their cell phones, the authorities detected their location and ambushed their hiding place at night. Fortunately, the monks abandoned their tent and were able to escape because of the madly barking mastiffs. Soldiers who carried out the insult opened fire. It has been unclear whether there was any casualty that night. Meanwhile, five of those monks remain on the run….

* * *

Incidents are always involved with various parties who, for good or bad, mutually influence each other. In turn, it is the interactions of a given incident’s different participants who keep the incident evolving. Of course, there are also those who are absent from it; and even among those who are at the spot, there are still absentees. Whereas there are those who, while having not been around physically, are by no means absent. They are the I whom Akhmatova describes, “I was with my people in those hours / There where, unhappily, my people were.”

There are different ways to refuse absence. I recall the words from some reading I had before: You assume the existence of darkness in the world. Yet, darkness does not exist. It is up to you to describe the degrees of brightness: twilight, dim light, tender light, sharp light, lightening…. Only when you lose light in the spectrum is there nothing left but the absence of light, the darkness.

Interaction is therefore important. It has been such a process of interaction through which I was shocked by the twelve Tibetan images that Losang Gyatso created/restored – as by those crucial moments in Jokhang and Labrang. Immediately, I downloaded the images from the artist’s website and reposted them on my blog. Concerned with the chance that readers of my blog might not understand them or had forgotten those moments, I added reports from foreign media and posted ten pieces of online news photos which I had downloaded during that intense time. Time has gone by, but those ten journalistic photos are still powerful. Human figures in them are real, locations are real, and what has happened is real. Nevertheless, despite the realism and immediacy of journalist photography, time changes, circumstances do too, and people tend to forget. In spite of being preserved in the memory of those who have been deeply involved, what has happened can swiftly disappear from the horizon. This includes foreign reporters. At the moment when the world was paying attention, they worked hard to seek out any bit of information on current events in Tibet. But their attention has since then shifted. Of course, their presence at those moments remains important. It is because of their presence that those moments actually took place. Otherwise, more such moments could have only sunk under the darkness unknown to the outside world. Fortunately, art is different. The moment restored in an artistic manner is a renewed representation and an unprecedented interpretation. While gaining for those moments the likelihood of eternality, it at least renders it more difficult to forget them.

Upon reposting the twelve Tibetan images by Losang Gyatso on my blog, I found a problem: Jokhang No. 4 and Jokhang No. 5 were nearly identical. I repeatedly compared them, wondering whether the artist might have posted the same image twice. I tried to pass on my concerns. Losang Gyatso quickly responded, saying that it was indeed a mistake but he had already corrected it. I returned to his website to download the new Jokhang No. 4, which looks to have been derived from someone’s profile among those news release photos. I used it to correct the posting in my blog. Surprisingly, three days later on October 9th, Losang Gyatso la informed me in a message that, based upon one of those news photos in my blog, he had come up with a new piece to replace Jokhang No. 4. I rushed to his website. Yes, the model after whom the newest Jokhang No. 4 is made is exactly the same monk who speechlessly stared at me with his teary eyes (and I stared at him with mine)…. Once more, I changed the posting in my blog.

Being able to participate in such an interaction comforts me, particularly because it was not too long ago I had written:

This is my first trip to be back in Lhasa after March 14th. More than five months after March 14th, once more I see the mountains that surround Lhasa, unique in their Lhasa shape; smell the air which belongs to Lhasa; and hear the accent which has its unique Lhasa rhythm…. Oh, I love Lhasa so much. On each of the trips to be back, every aspect of the city touches not only my skin, my flesh, but also deeply my soul! Nevertheless, Lhasa has gradually changed; it has become harder to talk about it. As if I had a toothache, I could not open my mouth because of the ache. I worry that the ache might one day become so severe that I would become completely speechless.

Oh, please do let me speak; let me pronounce my love for Lhasa. Lhasa is becoming imperfect everyday, Lhasa is being defeated everyday, Lhasa is deteriorating everyday! Let me tell all of this to the world, to my people, to my family, and to myself. But, this is after March 14th when I am finally back in Lhasa; with the pain crushing my heart and my spine, I realize that I has not been here since September last year, I has been absent from the most crucial time. Because I was not here, I have become an “other.” Because of my absence, I can only rely on the memory and testimony of those who were back then in the city. While I trust them, while their words are revelatory of covered-up realities, I still feel shameful and that something has been missing. Too much of the entangled feeling and emotion is with me when I am finally back in Lhasa.

As trivial as my participation in the interaction with Losang Gyatso and his new series is, it matters so much to myself who has until now felt very unsettled. Not being absent is a fortune, a comfort to one’s conscience. It must be the way in which Losang Gyatso has felt, I ponder. Before, his paintings were so beautiful that I could never absorb them all. Afterwards, these twelve shocking black-and-white images are so different. They are two kinds of participation: one which is in the past and the other in the present. From this perspective, the artist is the lucky one in both the past and the present.

While I was drafting this article, the interaction continued because my good friend Susan volunteered herself to translate it into English. Susan lives in America and has for years observed and studied contemporary Tibetan culture and society. She met with Losang Gyatso a few days ago, asking why he had decided to call those twelve images Signs from Tibet. Losang Gyatso explained that “signs” in the title of the new series can be just like road signs or those at the intersections to mark turns and dangers which might otherwise be neglected. As for these twelve images, they are derived from a specific time – March this year onwards; when the spring air remained chilly; and in the context which was not restrained in Lhasa but inclusive of Amdo, the rest of U-Tsang, and Kham. The uprising in the entire Tibet has been unprecedented since 1959; while shocking, it also sends a warning sign to the world.

Losang Gyatso further explained his intention behind the new series:

In forcing the image making process to be divorced from the emotional and narrative content of the events from which the images are derived, I hope to isolate the power and universality of the images while eliminating the two aspects of the video medium which tend to separate the subject and the viewer: its tendency to confine and distance its images through specificity of time and space, and its quality of not being able to separate the subject from its surroundings within the frame, thus diffusing the story with ambiguities and aesthetic concerns.

Yes, the conversion of images produced for their journalistic purpose into artistic expression is arguably a process to deflect the restraints of media. Nevertheless, since these artistic images are, through the way in which they are titled, made to be associated with Jokhang and Labrang, they bring me back to not only the most recent moment but also many other heroic yet sad events in the past. There is something extra in these two location names. If the artist had left the individual pieces of the new series to be numbered without them, would his artistic expression remain some form of voiceless silence? On the contrary, because of the location names of Jokhang and Labrang, the artist’s identity, passion, and position is revealed, and they rouse me to write down the words you are reading….

An interesting report appeared in The Guardian on October 1st. It regards the interview which its reporter did in Lhasa with Changchup Tsewang, the chief of the Religious Affairs Bureau in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR). The reporter of the newspaper asked about the whereabouts of those monks who had interrupted the organized tour of the foreign reporters in March to protest their lack of religious freedom. The incident was a headline in many newspapers around the world. Yet, Mr. Changchup Tsewang promptly denied the incident, insisting that he had never heard of anything like that which had happened in Jokhang. Rather, in his words, “Monks in the monastery are very content; they are very appreciative of the policy and the benefits from the government.”

Ah, it has only been a little bit longer than six months since March 27th. The officer who is in charge of all of the monasteries in the TAR at the highest rank has already begun to deny that moment. No doubt that he was lying. But, his lie is stupid! I cannot but be amazed – “Such a director who holds onto his piggy satisfaction, piggy appreciation! All he wants is the right to survive of a pig.”

On the other hand, lying repeatedly to forge reality has been the tactic they are best at. They already arranged a “regretful” monk to give a counter remark to another group of reporters invited from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan on June 3rd. The reporters were told that the monk’s name is Logya, which, as I remember, is the name of one of those protesting monks at that crucial moment in Jokhang on March 27th. According to the reports filed after the June 3rd visit, Logya said that he had been misled by rumors which he later regretfully realized as untrue. Those reports also mention that the monk once became very emotional, keeping his head down during the interview. Upon reading such descriptions, I feel the knife cutting through my heart.

It’s too late and suppression remains. Have they – I mean, that bureau chief and other big and small officials of different interests and ethnic affiliations – been a different kind of participant of the entire incident this year? Isn’t it the most barbaric violence that they have helped generating? Shouldn’t they also be documented for future reference? Shouldn’t they and their lies be screen printed on aluminum sheets for the world to see? Yet, what is the use to ridicule them? After all, their image would be too much like that of sidekicks – the kind who are absolutely shameless.

I wish to deny all of what has happened. Yet, no matter how much I want to deny, nothing is going to be the same, because “….all changed, changed utterly:/a terrible beauty is born,” “….for all that is done and said / We know their dream….” The “they” here have to be both the monks in Jokhang and Labrang and, modeled after them, the twelve Tibetan images that Losang Gyatso has recreated; it is the dream of these monks which is also ours.

* * *

The news of a surprising gift came when I was about to finish this writing: Losang Gyatso decided to send me a signed piece of the Jokhang No. 4! What a precious gift! I am moved and overjoyed, pondering how amazing such a performance art it is that Jokhang No. 4 is going to be forwarded through modern transportation from America, the remote Rawang Lhungpa (Land of Freedom) to Tibetans, to my guest dwelling in Beijing, the capital of the seemingly immense empire and the place of my exile! Moreover, I hope that I will in the near future be able to return to Lhasa again with Jokhang No. 4. Returning to Jokhang in the karmic cycle and Jokhang as a part of impermanence…. Oh, what does all of this mean! What do I have to give to reclaim its beauty?

October 3rd to November 4th, 2008 in Beijing

(Translated by Susan Chen)

1. Translator’s note: Woeser cites this and other lines from a Chinese translation of Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem. The English quotations herein are all from Anna Akhmatova Selected Poems translated by D. M. Thomas (New York: Penguin Books, 1976).

2. Translator’s note: Woeser cites from a Chinese translation of Easter, 1916 by William B. Yeats. The English quotation used here can be found at  http://www.online-literature.com/yeats/779.

http://www.online-literature.com/yeats/779.

3. Translator’s note: The testimony by Lama Jigme to which Woeser refers is available at  http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GZLIKmInP24.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GZLIKmInP24.