Allen Abramson, The Man Who Discovered Bill Girard

Allen Abramson Remembrance

By Glenn S. Michaels. 2016

Allen Abramson and I bonded because we were both in love with the same man.

Love is too sweet and respectable word to describe the intensity of our respective needs and desires.

Put bluntly, Allen and I were addicts. We were both hopelessly addicted to the art and person of Bill Girard, artist.

The Allen I knew, “my Allen,” probably told me the story of how he met Bill every single time I visited with him. It’s the same story you will read in his self-published memoir, compiled and written with the help of Nancy Malitz.

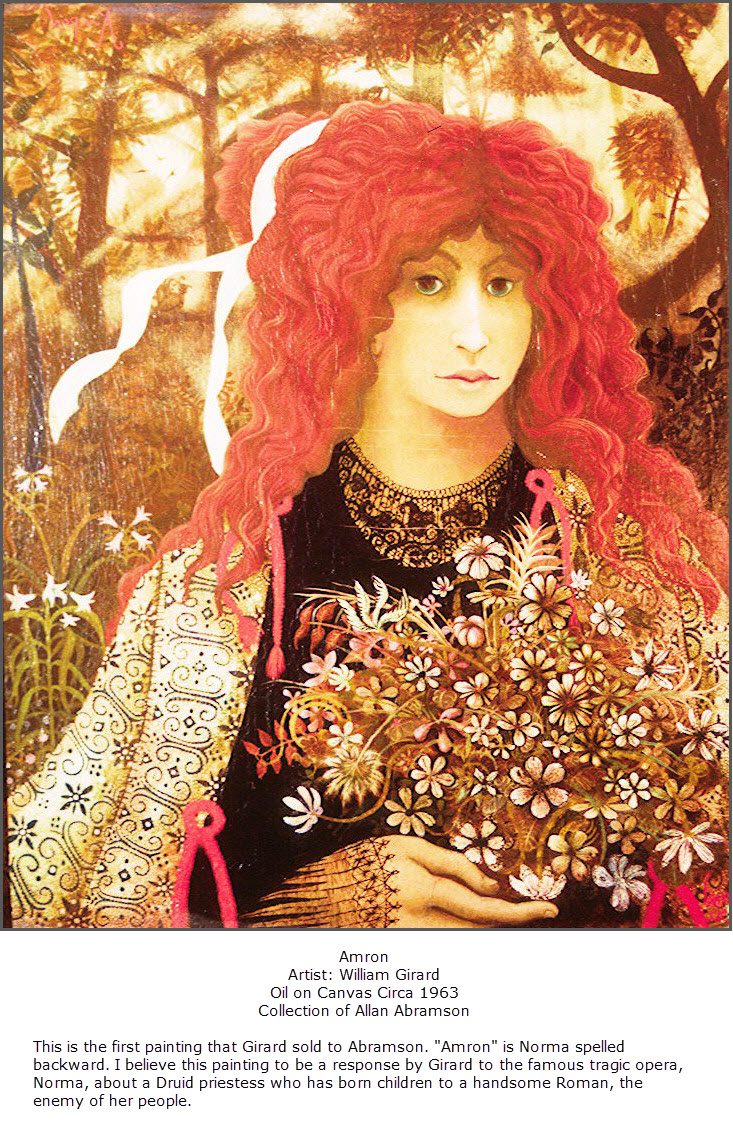

According to Allen, and I’m quoting from his memoir, “Shortly after the gallery opened, a young man by the name of William Girard walked in. He was carrying a little baby in one arm and a painting in the other. He needed money and wanted to sell the painting, so I took a look, and I was shocked to find out that was painted in this century. It was a beautiful thing… I bought it on the spot.”

The painting in question, Amron, was still hanging in Allen’s home when I last visited him, two years ago. Allen allowed me to photograph a large number of items in his collection over the years and by my count, he undoubtedly retained well over 100 items in his Girard collection until he himself was collected.

A few months before Bill died, in November 2010, I returned to Detroit to visit knowing that it would most likely be my last opportunity to spend time with him. As it happened, Allen knew that Bill was very ill and asked to see him. Apparently, he wanted to give Bill some money he felt he owed him. Since neither could drive, I chauffeured Bill to Allen’s house.

Allen was having a very hard time walking that day and used a cane. We sat in Allen’s living room, surrounded by art and most especially Bill’s art. I fetched water for them from Allen’s kitchen.

They hadn’t seen each other in quite a while. Bill had been very angry with his Allen over the years, for some of the various and predictable reasons that artists and their patrons quarrel.

This time, the mood was very different. Bill sat in Allen’s home and told him, face to face, how very grateful he was to Allen for making his life as an artist possible. For giving him the chance to create so many marvelous things. For the opportunity to bring his own art into the world and share it with others who appreciated it, not least Allen himself. He told Allen that he loved him.

After we left, Bill told me that Allen had given him much more money than he expected. He also reiterated his profound gratitude for the incredible gift that he had received from Allen.

The gift wasn’t merely that Allen bought, sold and kept Girard artwork. As many of you know, Allen was Bill’s patron: he paid him to make art for 15 years. When that particular relationship ended, Allen was apparently instrumental in helping Bill find employment with the Society of Arts and Crafts, later the Center for Creative Studies and today, the College for Creative Studies. To put this in some perspective, keep in mind that Bill had a total of one semester of formal post-secondary education at the Society of Arts and Crafts. When I arrived there, he was Professor Bill Girard.

It sounds sweet and easy. But it wasn’t. I can’t count the number of times Bill complained to me about Allen. Allen was demanding. Allen was unreasonable. Allen was pestering him to give him one piece or another. Allen had told some patron that he could have a particular Bill Girard piece that Bill had already promised to someone else. Allen said he sold something, but probably just kept it for himself. Oy! He complained.

Bill once told me that years before I had met him, Allen had arranged a gallery exhibit for Bill in NYC through the auspices of a well-connected friend.

At the opening, Bill apparently found the company of the wealthy, hoity-toity collectors in attendance difficult to cope with. So he decided to befriend the refreshment table. Refreshment tables, as you must know, rarely buy art. There he ran into an older couple helping themselves to copious servings of sundry tasty things.

The old couple told Bill that they really didn’t come to galleries to look at art. They came for the free food and drink.

Bill, in turn, decided that the gallery game wasn’t about art at all, and just refused to play for many, many years. Bill’s ego was bruised. But Allen paid for it. Literally.

Still, Allen could give as good as he got.

At some point, post new millennium I think, Allen was hospitalized. I don’t recall why. Bill visited him in the hospital. They hadn’t seen each other in a few years. “Hi, Allen, how are you doing,” Bill asked. “You’ve gotten fat,” said Allen.

At some point in Bill’s last months, Allen loaned him a particular piece of terra cotta sculpture, a kneeling David that Bill had made. Bill loved the piece, and wanted it beside him as he waited to be taken.

After Bill’s passing, like any addict deprived of his drug of choice, Allen seethed with irritation and frustration until the piece was returned to him. And that’s an understatement.

History records that Michelangelo had a turbulent relationship with his patrons, the Medici family. Allen didn’t have it much easier with Bill Girard and maybe, vice versa.

But what makes this quirky, prickly relationship so special to me – what should make it so special to others – is the fact that only my Allen Abramson, in all of greater Detroit, had the smarts, the luck or the wisdom to pluck a nascent artistic genius off the street and give him the freedom to create dazzling pieces of art.

Today, still, Bill Girard remains a complete nonentity in the art world. His life’s work is largely unknown. The range and extent of this astonishing autodidact’s accomplishments will most likely remain a mystery for decades, at least. But perhaps you have seen some of Bill’s work in Allen’s home.

I have been fortunate enough to travel fairly widely and to visit many major museums, in German, Italy, France, England, Switzerland, Spain and the US. I lived, for a time, in Florence, Italy. Though I have seen astonishing treasures in many places, none have astonished me more than the collection of Bill Girard pieces I saw in Allen Abramson’s Jefferson Avenue apartment in the early to mid-1980s.

Someday, I think - I hope - history will recognize Allen Abramson for his singular contribution to Bill Girard, to metropolitan Detroit, where Bill lived all of his life, and to the glory of art. He was Detroit’s Lorenzo de Medici as Girard was Detroit’s own Michelangelo. With this caveat, Bill and Allen had a far better sense of humor than their Italian renaissance counterparts and far less visibility.

I know, I know, this sounds incredibly hyperbolic. Nutsy, as Bill used to say.

Maybe it is. After all, I, too, am a Girard addict.

On the other hand, how many people do you know with a Rodin bronze at home? Allen was the only one I knew. And Bill’s work looked terrific next to it.

It’s easy to recognize a masterpiece after the rest of the world has stamped the thing with honors. It takes someone very, very special to recognize a masterpiece in something - or someone - that no one else has noticed.

Allen’s art education, as he often told me, really began when he met Bill Girard. Maybe. But I would argue that my Allen picked a diamond off the street when all the world saw only a pebble.

And for that I love and respect him. For that, I honor him and will always honor him. Faults included.

God Bless you Allen Abramson. Thank you for giving me my Bill Girard.