The Riddle of the Sphinx, Fowl Play and Other Engmas in the Graphic Art of Leonard Baskin'

THE RIDDLE OF THE SPHINX, FOWL PLAY AND OTHER ENIGMAS

IN THE GRAPHIC ART OF LEONARD BASKIN

About Leonard Baskin:

1922 -2000

In 1969, Leonard Baskin was the fourth graphic artist, after Reginald Marsh, Ben Shahn and George Grosz, to be awarded a Gold Medal by the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.1 He was a two-time recipient of the Tiffany Fellowship, received a Guggenheim Fellowship and was ultimately awarded six honorary doctoral degrees. According to the New York Times, Baskin was also the first American artist given the honor of an exhibition by the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Austria. 2 In fact, Baskin and his work were honored, internationally, again and again.

Baskin established The Gehenna Press, while in college. Through it, he printed over 100 books.

Baskin’s sculpture, watercolors, and prints have been purchased or otherwise acquired by many major art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, the Vatican Museum, the Smithsonian Institute and the Tate Gallery in London.

He was awarded commissions to create a bas relief for the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial and a Holocaust Memorial statue in Ann Arbor, Michigan. 3

|

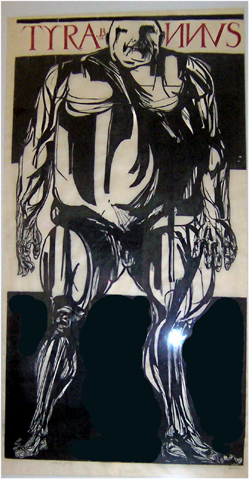

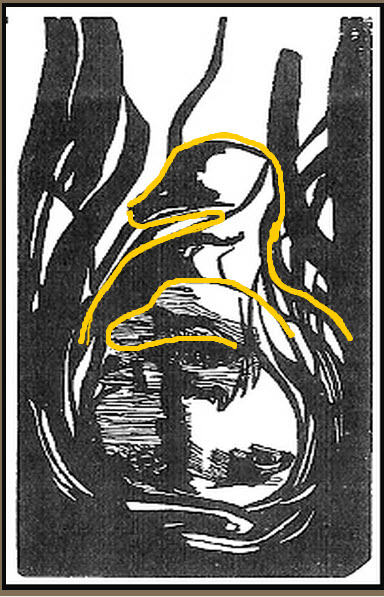

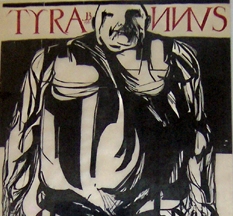

“That ain't art,” said the kid, “it’s a raw shark.” Raw shark? Sushi? "No." You mean the image exudes the ruthless power and danger of a shark? (TYRANNVS does appear “in the raw.”) "No." Turns out, the reprobate meant “Rorschach,” not “raw shark.” His point: TYRANNVS – and perhaps, by extension, much of Baskin’s graphic output – is actually a sort of Rorschach blot, capable of exposing a viewer’s unconscious interests and concerns. 5 Yeah, right. By my own admission, I was seeing things that, apparently, no one else had seen. So maybe I was just seeing things, right? A victim of my own overactive imagination? OK, maybe. And maybe not. The question is, was I seeing my imagination at work or Leonard Baskin’s? See and judge for yourself. As woodblock prints and Rorschach blots go, TYRANNVS is aptly named. It’s huge, measuring 74” x 39” (inside its frame). Looking at Mr. TYRANNVS, you’ve got to admit that if he were to do a Pygmalion and step off the paper he is printed on, he would be just the sort of guy a football coach, or a B-movie director, would love to recruit. On the other hand, coping with a TYRANNVS could prove to be a big challenge. However compelling, raw sharks, especially by artists like Baskin, sometimes turn out to be complicated, even disturbing. (A much older and far better known ink blot, Melencolia, by the famed German artist, Albrecht Dürer, has puzzled and compelled the attention of artists, admirers and intellectual sleuths for nearly 500 years.6) I first met TYRANNVS at the Bishop Gallery on Main Street in Scottsdale, Arizona. I was window shopping. He filled the window. The print immediately captured my attention with its raging, stone-cold fury. It was grotesque and true and beautiful. We flirted for a time. Eventually, TYRANNVS moved into our dining room. Its crisp, excoriating silence was simply fascinating. Granted, I understood neither the fascination nor the artist’s intent. TYRANNVS just felt meaningful. That status quo lasted for most of a decade. Then, one early morning while my wife was sound asleep, I propped myself against the kitchen doorway, coffee cup in hand, to visit with TYRANNVS. The visit was silent -- cerebral. We were just two entities, communing. Suddenly, shockingly, TYRANNVS seemed to fall apart before me as another, completely different image LEAPT from its loins into cognition.  Figure 3  Figure 2

Oh. My. God. A bird! There’s a bird.

Suddenly, the right hip of TYRANNVS had become bird, sitting - maybe nesting - on the figure's scrotum. (Now there’s a concept any psychiatrist contemplating a patient’s description of a Rorschach blot could have a field day with. 7)

Wow. How had I ever overlooked that? I couldn’t wait to show my wife. And yes, she saw it, too. For months thereafter I pointed it out to any visitor with an interest in art. Surprisingly to me, few of them could see it. I had to take a photo of the image and flip it horizontally for my guests, as they stood in front of the actual TYRANNVS, to help them see the “bird.” Of those that did, many seemed to think it was just a coincidence of some sort, a visual accident, like seeing shapes in clouds… or Rorschach blots. Huh. Nonetheless, I was convinced. And curious. What did it mean? Eventually, it occurred to me to call William Bishop, the art dealer and gallery owner who sold me the TYRANNVS. Some years earlier, Mr. Bishop had invited me to attend an opening for Leonard Baskin in his Scottsdale gallery. From prior conversations with Mr. Bishop, I knew that he and Leonard Baskin had been friends. He had even arranged for Baskin to make several presentations in metropolitan Phoenix a few years before the artist’s death. William Bishop, himself, is impressive: art savvy, business-shrewd, well-read and steeped in culture. He was a friend of the famed Southwestern artist, Fritz Scholder 8, whose work he also sold. Through him I was also introduced to the former star of the Metropolitan Opera, Isola Jones, then adjunct Voice Faculty at South Mountain Community College in Phoenix.9

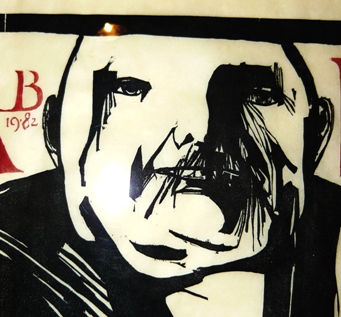

But, it turned out, Bishop, too, had been unaware of the bird hidden in TYRANNVS’ loins. So I took an extended lunch hour from the office to visit the library of the Phoenix Art Museum. A librarian led me to the folders that embraced a lifetime of Baskin clippings from newspapers and art publications. One by one, I scanned and winnowed through opinions and insights. There were laudatory reviews, seductively saccharine assessments and impenetrably abstruse analyses that might just as well been written in Attic Greek. A small mound of newsprint had been gathered together in homage to the prints of a singular artist. I saw plenty of references to the prizes and honors, museum exhibits, gallery shows and special purchase awards that the artist had accrued in an active, busy and fascinating life. Wow-wow. Here was an artist so famous that even the Phoenix Art Museum owns one of his massive bronzes. Much of what I scanned I knew already. Leonard Baskin had lived a long life, filled with acknowledgements, honors and recognition. He wrote with incision and clarity about his work and opinions. His graphic output was widely disseminated: as individual pieces of art, as book illustrations and, collectively, as graphic essays collected into books. There were many references to the fine art press he had founded: the Gehenna Press. Its products, too, had become and remained eminently collectible. What I didn’t find was the slightest crumb of clarification about any "hidden" images or what they might have meant to the artist or his work. This struck me as exceedingly curious. Curious, because art is a form of communication and Baskin, as an immensely successful artist, had clearly been an excellent communicator. To start, he was multilingual. He wrote in English and added Hebrew texts to many of his prints. He also studied art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France and at L'Accademia di Belle Arti, Florence, Italy. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, spent more time in Italy and later, kept a home there. 10,11 Chances are he spoke and read Italian passably well. He also, certainly, spoke and read Yiddish. After all, he was the son of a rabbi and had spent his early school years in a yeshiva. Moreover, he was a professor at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, for decades. Professors are generally supposed to be good communicators; that is their job. (I have, however, encountered exceptions to that rule.) As the son of a rabbi (Hebrew for “teacher”) Baskin had probably picked up some of the tricks of the trade from his father. Then, too, he had equally impressive collaborators and friends. Folks like, say, Ted Hughes, who later became the poet laureate of England, for whose publications he frequently contributed images. Sylvia (Plath), Hughes’s wife, even wrote a poem, Sculptor, dedicated to Baskin.12 (Interestingly, Plath and Baskin both taught at Smith College in the late 1950s. So did Paul Roche, whose respected translation of Oedipus the King was published in 1958.) It’s fair to say that just about everyone interested in print making and figurative art during the long years when abstract expressionism and its children controlled the highest profile walls in America and Europe would have seen or heard something about Baskin and his work. Is it possible, is it credible, that Baskin never mentioned, intentionally or unintentionally, the insertion of hidden or, perhaps, camouflaged figures within his images, if in fact he intentionally created them to begin with? And how is it that no one else had noticed a 21-inch long "bird" in a print, TYRANNVS that stands over six feet high? So either I really was “seeing things,” per the reprobate upstairs, and in possible need of professional psychological insights or I was seeing something that all knowledgeable experts and the general public had completely missed. The latter option seemed, well, crazy. Maybe hundreds of thousands of people – art lovers – had looked at Baskin’s work over many years, in magazines, books, museums and galleries. Only I seem to have noticed “hidden images.” Suddenly, TYRANNVS wasn’t just a live-in friend and intriguing art print that I happened to have and enjoy in my dining room. It had become the door to a mystery. Maybe, to an obsession. I needed to prove, at least to myself, that I wasn’t nuts. For the first time, I began to think about the image. It finally occurred to me to wonder what the word “TYRANNVS,” displayed so very prominently at the top of the image, really meant. “TYRANNVS,” I found, is one of several variant spellings, in Latin, of the Greek word: Τύραννος. The Encyclopedia Britannica describes a tyrannos as “…in ancient Greece, a ruler who seized power unconstitutionally or inherited such power.” The scholar, Anne Saxonhouse, describes the tyrannos as a new (type of) ruler; someone whose status as ruler was neither hereditary nor based on long-standing traditions and relationships. She describes the tyrannos as a guy in search of freedom, a fresh start, a break from tradition, and for that very reason, illegitimate.”13 TYRANNVS is also half the Latin transliteration of one of the best known of all classical Greek theater pieces: Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, by Sophocles. The full title of the Latin transliteration is Oedipus Tyrannvs. Translated into Latin, it is Oedipus Rex, .a title widely known by aspirants to a classical European education for whom the study of Latin and Greek was a necessity. The standard English translation is Oedipus the King. 14 As it happens, Baskin contributed the cover art to a new translation of the Oedipus plays by Robert Bagg, published in 1982, the same year that Baskin incorporated into TYRANNVS. 15 Scholars estimate that it was written sometime around 432 B.C. The origins of the story are far older. 16 It is one of three plays about the life of Oedipus and his family that Sophocles wrote. Sophocles’ Oedipus plays are tragedies. Together, they represent an impassioned argument for the power of humility, virtue, social and personal responsibility to elevate and re-invigorate society (the state) particularly in dire circumstances. These are similar to the themes that Baskin would have encountered and discussed, as a yeshiva boy and Rabbi’s son, in the Torah and Old Testament. You can imagine the special resonance they would have for a profoundly Jewish artist in the years after WWII, a period of interlocking conflicts and “cold war;” the after-shocks of unimaginable duress and mayhem. As Sophocles tells it, Oedipus is doomed even before his birth. His father, Laius, the king of Thebes, had heard from an oracle before the birth of Oedipus, that his own son would one day kill him. After Oedipus is born, Laius orders the baby killed. Not unlike baby Moses, baby Oedipus is saved by deceit and ultimately ends up as the adopted son of another, the king of neighboring Corinth. When, as a young man, Oedipus learns from the oracle at Delphi that he will kill his father and bed his mother, he flees the city and parents he knows and loves. Running from fate, Oedipus encounters his biological father, King Laius, on the road that leads to Thebes. Laius, in a chariot led by a groom and accompanied by four others, attempts to force the unknown pedestrian off the road. Oedipus strikes back at the groom, at which point Laius clubs Oedipus on the head with a “double-pointed” goad. Stalwart Oedipus returns the blow and knocks the King from his chariot, stunned. Oedipus then kills Laius and four of his bodyguards, presumably in self-defense. One escaped. Simply stepping out of harm’s way wasn’t a viable option, it seems. Farther down that road, Oedipus subsequently saves the city of Thebes from a murderous sphinx and is chosen as the new ruler of that city. He then marries his mother, with whom he has four children. Oh happy days. 17 The phrase, "Oedipus complex" was coined by Sigmund Freud, the Viennese psychiatrist, to describe a male child's antagonism toward a father as a competitor for his mother's attention.18 That little gem of insight derives from the story of this same Oedipus. On the sad day that Oedipus finally learns the truth about himself, he literally blinds himself in a spasm of shame and misery. In TYRANNVS, I concluded, Baskin depicted the blinded Oedipus. Black ink - blood - streams from Oedipus' eyes, rolls down his cheek and onto or through the rest of his huge frame. Unfortunately, figuring all this out didn't help explain the presence of a bird in the loins of the TYRANNVS. At least, not at the time. Meanwhile, it seemed that if Baskin has hidden one image in TYRANNVS, he might have hidden others. I kept looking. I didn't have to look far. Just above the head of my initial find (Figures 2 & 3), I spied a second, camouflaged bird-like shape.   Figure 4 Figure 5: Detail View

Figure 4 is a horizontal view of the figure's left arm. The bird's head, beak and wing are clearly delineated, in white (i.e., as negative space). The wing is folded against the rest of the body. Figure 5 shows that bird close-up. The “camouflage” consists of multiple shapes similar to the birds in Figures 4 and 5. For example, immediately above the bird’s head in Figure 4, is a negative space shaped like the bird’s head in reverse. Likewise, above the bird shown in Figure 5, there is a flattened negative shape (seen in Figure 4) that roughly echoes its appearance.

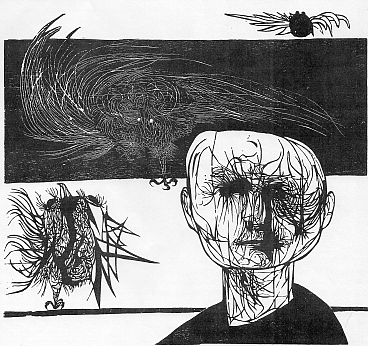

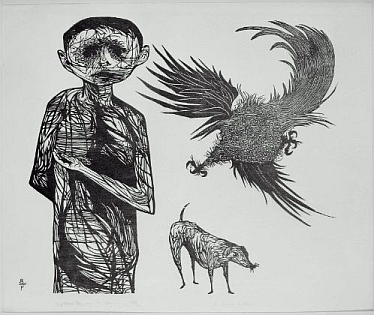

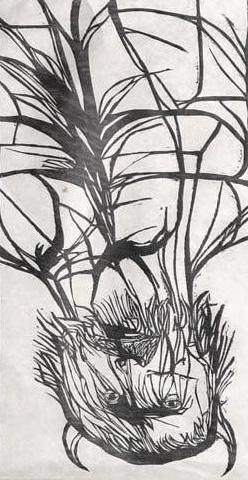

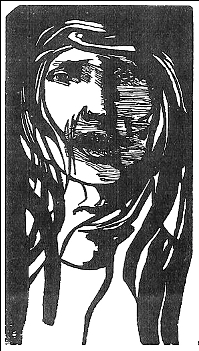

"Oh come on, Glenn. Are you sure those are birds? They don't look like birds to me," said an artist friend of mine. Baskin periodically gave himself license to re-imagine the essence of birds and he tried his hand at that task again and again. The Tormented One (Figure 6) and Frightened Boy and his Dog (Figure 7) demonstrate this intention, but are merely two of many such examples.

Figure 6: The Tormented One

True, a bird drawn by Leonard Baskin doesn't always look like a bird you've glimpsed in a pet shop, at the zoo or on a hike. It might not look anything like a bird. But, sometimes, Baskin's almost magical distillation of "avian qualities" turns lines and ink into an unmistakable symbol for bird, anyway.

Figure 7: Frightened Boy and his Dog Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Figures 6 and 7 display textures and qualities that we associate with birds. They're simply remixed. These are images filled with the artist's persona and vision, not a literal description. Sometimes, his lines give us soft hair- and feather-like textures. At other times, his lines and shapes are sharp as claws. Anyway, two birds in one TYRANNVS were enough to prompt a visit to the Burton Barr Public Library in Phoenix. After all, if Baskin had hidden images in one piece... There I found and inspected The Complete Prints of Leonard Baskin: A Catalogue Raisonne 1948-1983. (It’s one of those valuable tomes that can only be viewed in the velvet silence of the Rare Books room on the fifth floor of the library, by appointment.)19

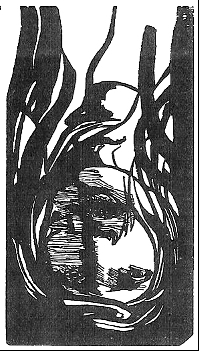

I saw no references to hidden images in that book, either. But I found ample evidence that Baskin had indeed hidden images in other prints. Let's start with Baskin's image, Captain Ahab, a major character in the great American novel, Moby Dick, by Herman Melville. Take a look.

Figure 8 Here you see the complete image. Now look at a detail view, below.  Figure 9 Figure 9 is a detail of the left breast of Captain Ahab, rotated 90 degrees. It's hard to argue that this image doesn't look like a bird. At best, it would seem the counter-argument is that the resemblance is mere happenstance (aka horse feathers). Let's keep looking.Desdemona, in Figure 10, is another example of Baskin's "fowl play." Seen right side up, Desdemona (the faithful wife that Othello is tricked into murdering in Shakespeare's play of the same name) looks fearful. Her mouth is agape. Much of her face is in shadow. The anguish in this image is palpable.  Figure 10

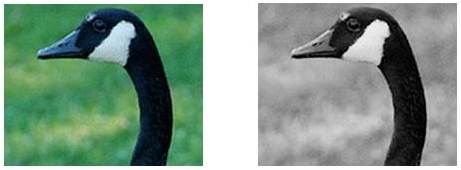

Below, you see the same image, inverted. Notice anything... different? Does anything "pop out" at you? Figure 11 If you don’t see anything special about poor Desdemona, except that she is hanging upside down and seems rather upset about it, study Figure 12, below, a detail of the same image, enhanced with outlines.

Figure 12

Compare what you see within Figure 12 to the images in Figure 13, below.

Figure 13 Figure 13 depicts the head of a Canadian goose, first in a full-color photo and then again, using the same photo, but will all of the distracting color removed. The shape of the goose head is remarkably similar to the shape that we see rising from Desdemona's chin in Figure 12. More horse feathers?

What's more, there seems to another, similarly shaped goose head below and ever so slightly to the left of the first. The outline of this white headed goose is, however obscured by hatching. The higher shape is erect and proud. The second seems “submissive.” The area around its eyes is black. Shakespeare’s Othello is the story of a “dark-skinned” Moorish general (generally considered to have been “African”) in the service of the Republic of Venice and his adored and adoring Caucasian wife, Desdemona. By the end of the story, Othello has been manipulated into murdering his wife on the ill-founded suspicion of infidelity. Once the facts proving malicious manipulation are revealed, Othello kills himself, as well. Who can say what Baskin might have been thinking? Perhaps the more erect shape was created intentionally while the second reflects the guidance of his subconscious mind. In any case, note for the record that Canadian geese have black heads and necks with a large, single spot of white beside their eyes that wraps under the neck. In Figure 6, above, Baskin gave us three very different, very abstract images with distinctly birdlike qualities. Their appendages have a feathery quality. The two lower images both display a single claw. The point is not that they are birds, but that they embody abstract qualities that we associate with birds. When I looked again at TYRANNVS, still hunting for clues that Baskin might have left, I found a hint of that same abstract quality in, of all places, the figure's head. More specifically, its eyes.

Consider that when Leonard Baskin worked on the woodblock that produced the print, he likely flipped it around to work on various areas or laid it flat and walked around it. After all, the image is over six feet high. Apparently, woodblocks (wood block prints) of this size were traditionally made using multiple blocks of wood to print on a single sheet. Baskin, however, having a background as a sculptor, decided to create woodblocks using a single, large block.21 Thus, it is likely that he would have had to address the piece from different angles to work on it comfortably. This means that the artist had the chance to see David Chorlton was born in Austria and was taken to England within weeks, before he could protest. After growing up in Manchester, he moved to Vienna in 1971 and seven years later he came to Phoenix. That leaves twenty-two years of writing, operating with small presses, and carrying on a parallel life as a visual artist. (Please visit ARTifacts, to view several of his paintings.)

Publications: David Chorlton's publications are poetry collections. They include:

ASSIMILATION, a recent chapbook from Main Street Rag Several of these, and others, are accessible through Amazon.com, but David Chorlton is the most reliable source at 118 West Palm Lane Phoenix AZ 85003 Email: As is clear from looking at Figures 11 and 12, simply changing the angle at which an image is viewed can be incredibly revealing. Or, from the opposite perspective, remarkably concealing. How else could one explain why a 21-inch long bird in the thigh of TYRANNVS went unnoticed, by everyone, for so very long? As you can see in Figure 15, Baskin dated the image 1982. As of this writing, in January 2011, 30 years have passed since this piece was created. And still, it appears that almost no else one has noticed this otherwise "obvious" image, right in front of a viewer's eyes. Speaking of eyes. Let's take another look at the eyes of TYRANNVS, by changing the angle of view, again. Figure 15

What we see are two shapes that scarcely resemble eyes when viewed from another angle. Odd, isn’t it? Do you see anything birdlike about them? It's a question of perception, isn't it? After all, we can't ask the artist now. To be absolutely certain, check out Figure 17, a closely cropped detail view of those “eyes.” Figure 16

Now look at the following photo of a kingbird (Figure 17). Figure 17

The smaller of the two images in Figure 17 looks oddly similar to the kingbird in Figure 18, wouldn’t you say?

Here's what Wikipedia had to say about the kingbird. “The genus Tyrannus is a group of large insect-eating birds in the Tyrant flycatcher family Tyrannidae. The majority are named as Kingbirds...

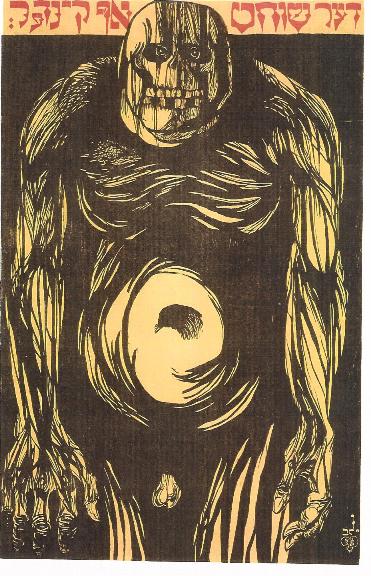

“These birds tend to defend their breeding territories aggressively, often chasing away much larger birds. The genus name means ‘tyrant.'"22 A skeptic might call the correspondence between these images and the associated description "serendipity." My response: “Horse feathers.” Examine one more hidden bird image, in The Specially Ordained Slaughterer for Children (Figure 18). After that, we're on to another species entirely. Figure 18

This ghoulish image was featured in "Leonard Baskin: The Holocaust and Other Prints and Sculpture" at the West Valley Art Museum, in 2000.23 By the way, is that a birthmark in the belly of the beast? Squint at it. Tarnation, it sure looks a lot like a bird's head, seen in profile. Horrors, not again! So, if Baskin did in fact hide images of birds in sundry images, couldn’t he have done the same with other species, too? He could and, I believe, he did. Admittedly, some examples seem more obvious than others.

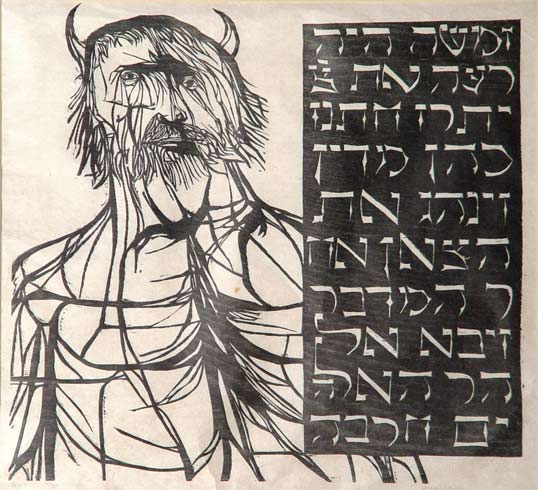

Baskin’s image of the biblical Moses (Figure 19) depicts Moses with horns. Students of European art history will likely have seen (pictures of) Michelangelo’s magnificent sculpture of Moses, with horns, created for the Mausoleum of Pope Julius II. For centuries, Moses (and by extension, the Jewish people) was portrayed as a minion of Satan inside Christendom due to a mistranslation of Exodus 34:29. The “rays of light” that shone from Moses’ head when he returned from Mt. Sinai with the ten commandants a second time were described in the Vulgate translation as “horns.” 24 That a Jewish artist would also give Moses horns seems a little surprising. Perhaps it is a reminder that Moses meant different things, at different times, to many. Figure 19

Flip the image 180 degrees and there’s another surprise. Figure 20

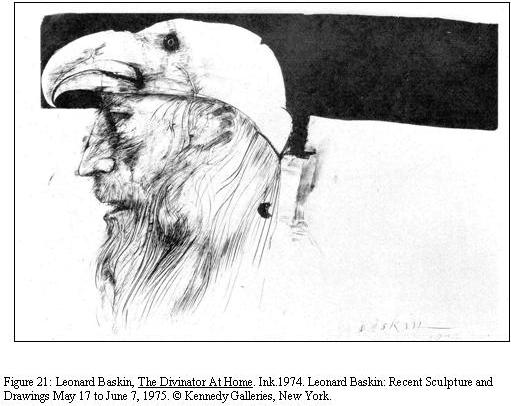

A plant grows from Moses’ throat. The leaf shapes are too complex, too clearly shapes, as opposed to the lines that traverse the rest of the figure’s chest, to be anything other than intentional. In The Divinator At Home (Figure 21), presumably a self-portrait of sorts, Baskin gives us a man with a bird on his mind. His thinking cap appears to represent an eagle head. (You don’t suppose the common English term “eagle eye” might have been in the back of Baskin’s mind, do you?) Figure 21

A divinator “divines” the hidden significance of things and, in some cases, predicts the future. The root of the word, divine, suggests a God-given or God-like power to understand, see or hear what few others can. William Blake, the great English artist, print maker and poet, whose self-published work is said to have given Baskin the idea of creating his own press and publishing his own work, frequently claimed that he conversed with spirits and angels. 25, 26 How could I help but notice, in the area just to the left of this figure’s ear, a profile, in miniature, with the same straight nose as Baskin gave the larger head?

Figure 22

The dark spot near the left border of Figure 22, defines the bottom of this figure’s nose, upper lip and chin. No eye is shown, although some slight hatching underneath the brow provides a faint suggestion of depth. All of which brings us back to the unresolved mystery of TYRANNVS. What had Baskin been up to with this massive print? Early on, I had seen but felt uncertain about my attribution of “feline qualities” to certain elements of image. Hint: Think “negative space.

Look at the left side of the image, just below the clavicle. Here’s a detail view. Figure 23 Figure 24

A cat. Really? Well, perhaps the fractured silhouette of a cat, with its tail wrapped around itself. Aficionados of felines may be more familiar with this, than say, a dog owner. It was, however, my second discovery of a shape with “catitude” that unlocked the possibility a real interpretation of Baskin’s intent. Look closely at TYRANNVS’ belly. Notice the whiskery shapes? Can you see a cat’s eyes?

Figure 25

The (white) feline shown in Figure 25 is snuggled right up against the chest of the big black bird (shown in Figures 3, 26). It turned out to be a significant clue to the puzzle of Baskin’s TYRANNVS. If it doesn't seem obvious, don't worry. It isn’t. Leonard Baskin didn’t, presumably, intend it to be obvious.

Figure 26 Now for a bit of context. Recall that Oedipus came to fame in Thebes because he saved the city from the sphinx. According to Sophocles, that nasty sphinx asked the same riddle of every would-be visitor to Thebes who happened by. Travelers who couldn't solve the riddle correctly traveled no farther. The sphinx ate them. For the sphinx, the living was easy. But you can imagine what this meant to poor Thebes' reputation with tourists and for its tourism industry as a whole. This state of affairs was exceptionally dramatic and traumatic, for everyone involved except said sphinx. Until, that is, a young man named Oedipus, trying to evade fulfilling the prediction of the Oracle, stumbles into the story. Here, Oedipus models the role later taken up by Sam, the Hobbit, in the popular Lord of the Rings trilogy, a 20th century vision of darkness. The dramatic situation requires a heroic protagonist, a deadly predicament and an almost certain outcome. Sam, a diminutive fellow who finds himself face-to-belly with the huge, hungry spider, Shelob, wields a small, but uniquely powerful sword. It saves his life and sends the spider into hiding. Oedipus faced with a similar, though far more literary challenge, wields a remarkably sharp intellect, instead. He correctly dissects the riddle of the sphinx and lives. The sphinx, suddenly bereft of its riddle and off the public dole, kills itself. Thebes was saved.

Figure 27: Oedipus and the Sphinx Gustav Moreau, 1864. Metropolitan Museum of Art

As you can see, the sphinx that Oedipus confronts combines the body of a feline with the wings of a bird and the breasts and face of a woman. While there should always be room for doubt, the tight juxtaposition of an image with “feline qualities” with that of a bird, inside an image of Oedipus, the man who outsmarted the sphinx, scarcely seems like the product of my overactive imagination. In Moreau's image, the body of the sphinx is placed just below Oedipus' thigh and rises to his shoulder. Baskin's "hidden" bird and cat appear to cover much the same territory, give or take a bit. Mere serendipity isn’t a credible explanation for the many signs that suggest a purposeful series of choices and decisions by the artist. In life, as in Oedipus Tyrannus, human beings are the totality of all they have done, all that has been done to them and all that their ancestors did, as well. This is the "what" of their existence. Who we are is defined by our individual response to that "what." The apparent representation of both a bird and a cat (Figure 26), visually conjoined within TYRANNVS, could easily be an allusion by Baskin to a key ingredient in the story and life Oedipus: the sphinx and its riddle. It is, itself, a visual riddle. Alternately, it might be that the artist was simply playfully re-combining the same elements of the Oedipus story in his TYRANNVS that Gustav Moreau and other artists had used in their depictions of the same image. So why did Baskin conceal images in his work at all? That is, why didn't he point them out, in the public arena, or in his own published work? Perhaps he was testing his audience. Or warning us. Do any of us - experts, novices or amateurs - really see everything in front of us? Do we see as much as we think we do? Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus is literally filled with riddles. There is the riddle of the sphinx. The Oracles’ predictions make a riddle of Oedipus’ heritage. Then there is Oedipus, the king of Thebes, who must solve the riddle of why his city and its citizens are suffering at the hands of the gods. The answer to that riddle ultimately prompts Oedipus to destroy his own eyesight, in shame and remorse. There is an ironic consonance between Baskin’s image of a blind Oedipus and our own inability to see what appears directly before our eyes, as this essay attempts to demonstrate. We are all too often blinded, like Oedipus, by assumptions that amount to nothing more than arrogance, ignorance or, perhaps, laziness.27

Those that recognize the limits of their sight - of their own insights – may, unlike Oedipus, avoid falling afoul of their own arrogance. Oedipus Tyrannus actually opens with Oedipus’ quick, public and heart-felt condemnation of the man who murdered King Laius, his predecessor on the throne to Thebes, to banishment or death. All too soon, Oedipus discovered that he, himself, had done the foul deed. The same mercurial temper that prompted his murder of the stunned Laius, his father, and his ignorance of his own ignorance, made him blind while he had eyes able to see. Our inability to see what Baskin placed in front of our eyes must be a warning to us all. “The human figure is the image of all men and of one man. It contains all and it can express all. Man has always created the human figure in his own image and in our time that image is despoiled and debauched…. The forging of works of art is one of man’s remaining semblances to divinity….I hold the cracked mirror up to man.” (Leonard Baskin) 28 One way or another, it seems that Leonard Baskin was posing a riddle of his own, a very graphic riddle at that, to his audience. Glenn Scott Michaels Phoenix, Arizona January 18, 2011  gsmnem@gmail.com. gsmnem@gmail.com.### Footnotes 1. American Academy of Arts and Letters, Award Winners. (See; 2. Art: Masters, Past and Present. John Canaday. February 14, 1970. The New York Times. 3. " 4. Lacking the proper equipment, I took this photo of my TYRANNVS print at an angle to reduce glare. I purchased the print from the Bishop Gallery of Scottsdale, Arizona in 1992, from William Bishop, owner. 5. Webster’s New World Encyclopedia, page 961. Copyright 1992; Random Century Group Limited and Simon & Schuster Inc. First Prentice Hall Edition 6. MELENCOLIA I.1, 7. Is the bird keeping the “egg” warm or grabbing the figure “by the balls,” as the vernacular would have it? Either way, this image suggests an association between the bird and the seat of male sexuality. In many cultures and languages, birds are associated with the sex act. In English, we speak of flipping someone “the bird,” a gesture that displays an extended middle finger from an otherwise closed fist. The same gesture is commonly used in conjunction with the vulgar English expression “Fuck you.” In German, the noun for bird, Vögel, when used as noun, is commonly understood to be a vulgar reference to coitus. In vulgar Italian, Uccello, the common word for bird, also means “penis.” ( As will later become clear, sex (i.e., the act of coitus) and the results thereof are primary concerns in the story of the individual that TYRANNVS represents. 8. 9. 10. 11. I met Baskin while a student at Studio Art Centers International, in Florence, Italy, through the director and co-founder, artist Jules Maidoff. Maidoff told me that he and Baskin had travelled to Italy at the same time, both having received scholarships. He also told me, at that time, that Baskin kept a home in the area. For more on Maidoff, see: http://www.julesmaidoff.com/resume.php#2. 12. Dictionary of Art & Artist, Leonard Baskin, 13. The Tyranny of Reason in the World of the Polis, Arlene Saxonhouse, University of Michigan. The American Political Science Review, Vol. 82 No. 4, December 1988 14. Note that the letters NNV in TYRANNVS appear to be printed in reverse, as if we were seeing them in a mirror. Although I have yet to explore the typographic logic and implications of this choice, I suspect that Baskin’s intention was to signal an intentional subversion of standards and expectations for this image. 15. “Oedipus the King” Sophocles. Translated by Robert Bagg. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA Copyright 1982 Note: Baskin also personally printed, via The Gehenna Press, Bagg’s translation of This citation suggests just how freely Baskin allowed himself to play with his own identity. If he took such liberties with himself, it seems most likely he would not have hesitated to play with other forms of identity. See the original citation, in full, below.

16. “The Oedipus Plays of Sophocles,” Translated by Raul Roche; New American Library, Times Mirror. Copyright 1958. 17. Here, too, the parallels to the story of Moses are intriguing. After all, Moses also commits murder, also flies from his royal adoptive family and the country it rules, and also ends up “delivering” his native people from a malign and powerful enemy, Pharaoh. 18. “Webster’s New World Encyclopedia”, page 823. Copyright 1992; Random Century Group Limited and Simon & Schuster Inc. First Prentice Hall Edition. 19. “ 20. My wife, an ASID commercial designer, points out that a second bird seem to sit just to the left of the bird identified in Figure 8. Its head is somewhat obscured. In addition, it strikes me that the abdomen of Ahab in this image could be construed as the head of whale or large fish. My wife disagrees. 21. Leonard Baskin: Monumental Prints, 22. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingbird – (November 27, 2010 at 23:43). 23. 24. The Anti-Semitic Origin of Michelangelo's Horned Moses, Stephen Bertman. Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies - Volume 27, Number 4, Summer 2009, pp. 95-106 (Abstract: http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/shofar/v027/27.4.bertman.html) 25. “Leonard Baskin.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. (January 22, 2011). 26. “Blake, A Biography.” Pgs 329-330. Peter Ackroyd. Copyright 1995 Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. New York. 27. Much the same point has been made, with trenchant effectiveness, in The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Copyright © 2007.The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. ISBN: 9781400063512 28. “New Images of Man” page35. Peter Selz. 1959. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

|

New Insights: Related and Unrelated |

Obvious things are sometimes the hardest to recognize.

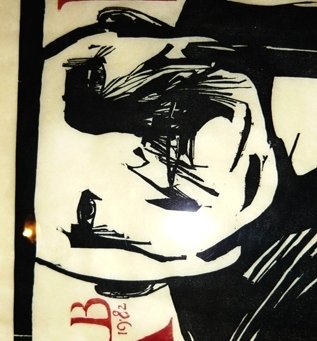

1A. Title and Baskin's mark, with date.

1B. Reversed - aka mirror imaged - letters: NNV, followed by an S.

2. Detail of Baskin's mark.

3. Baskin's handwritten pencil signature, as it appears at the bottom of the TYRANNVS print.

Did you notice that the three letters to the left the head of TYRANNVS, are the capital Roman letters, NNV, in reverse? They’re not terribly subtle, after all.

However, the logic that prompted Baskin to present those particular letters in reverse has long puzzled me.

Quite recently, however, I noticed something that I should have observed years ago. Baskin’s mark (1 & 2), at the top of the Tyrannus print, is not (just) a capital “B” with a date below it. It is in fact, a reversed capital L joined to a capital “B.”

And why does that matter? Because it establishes a pattern. When Baskin cut the letters NNV into his woodblock, he was not acting on a whim. It was not a "singular" choice dictated by aesthetic necessity. By incorporating a reversed letter into his personal mark, as well, he demonstrates a significant and personal attachment to such representations. Baskin isn’t merely representing letters of the alphabet used to define a title or name. He is rendering them as symbols.

Context is everything. In this print, TYRANNVS isn’t just a title. It is an identifier of something quite specific. It refers to Sophocles’ Oedipus.

TYRANNVS is half the Latin transliteration of one of the best known of all classical Greek theater pieces: Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, by Sophocles. The full title of the Latin transliteration is Oedipus Tyrannvs. In my youth, it was commonly known by the Latin translation, Oedipus Rex. The standard English translation is Oedipus the King.

As it happens, Baskin contributed the cover art to a new translation of the Oedipus plays by Robert Bagg, published in 1982, the same year that added to his mark in the TYRANNVS print.

The point is, this TYRANNVS identifies a very specific personality in literary history. Likewise, Baskin’s own mark identifies a very specific person in modern (art) history.

Is Baskin implying that he, an artist (of significant accomplishment) and the monstrous, tragic, ill-fated, self-blinded King Oedipus have something in common? Something, essentially “backwards?” And, if he is, should that be surprising? Why shouldn't a sensitive human being whose life and personal story intersected one of the most destructive wars in human history, an intellectual and a professor in a profoundly myopic and barely self-conscious culture, find some semblance of himself - of his extended selfhood - in another equisitely rendered representative of the human condition?

Or was Baskin simply underlining the point that I previously suggested might have motivated his choices regarding TYRANNVS? That relatively slight changes of perspective – twists - of context, are sufficient to render otherwise, relatively obvious things virtually invisible?

As noted in my essay, Baskin was Jewish and the son of a rabbi. That means he would have studied Hebrew as a prerequisite to celebrating his Bar Mitzvah – a religious and cultural rite of passage signifying entrance into (spiritual) maturity. Since his own essays demonstrate a profound interest in language, it seems quite likely that the young Baskin was steeped in Hebrew and traditional Jewish cultural references.

And why does that matter? Well, consider this.

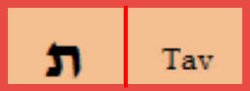

According to  www.ancient-hebrew.org, the Hebrew letter “tav” looks like this:

www.ancient-hebrew.org, the Hebrew letter “tav” looks like this:

Below find a detail from the right hand of TYRANNVS, on the left side of the print.

Now, to me, that shape in the yellow circle looks a whole heck of a lot like a mirror image of the Hebrew letter “tav,” shown above.

Could it be another example of the pattern of reversed letters discussed here? I think so.

As I don’t have any Hebrew training, I can’t yet conjecture what that character’s appearance might imply.

Are there other hidden Hebrew letters? I suspect so.

I'm working on it!

Glenn S. Michaels

June 10, 2018